[ad_1]

This is why teachers deserve appreciation every day.

USA TODAY

Mary Parker Poole taught fifth grade. A lot of the kids didn’t like her because she was old. But I thought she was kind of cool. Especially when she taught our Armistice Day lesson by telling us how the 15-year-old version of herself felt when she learned the War to End All Wars was over.

She’d actually written a book. Her husband, who had died a few years earlier, had invented a treadle-powered windshield wiper in 1927. She showed us his patent, No. US1629734A. It was my first lesson in intellectual property.

Bea Perkins taught seventh-grade biology and homeroom. She was so appalled by the sheer adolescent ignorance of sexuality she overheard in the halls every day that she defied the school board’s wishes and taught us what most of our parents wouldn’t.

She taught it in cold, clinical detail.

She’d seen too much teenage promise derailed by unplanned pregnancies and knew that knowledge trumped ignorance, even when it came to uncomfortable subjects.

Conrad Knudsen introduced me to J. Alfred Prufrock, Billy Pilgrim, and Capt. John Yossarian. A year later, he was working as an adjunct and was my college freshman English teacher. He introduced me to more of his friends like Donald Barthelme, Shirley Jackson and Ring Lardner. He taught me to dissect their prose line-by-line and word-by-word, looking for meaning, making sure I took into full account the context of their times.

He did the same to me when he graded my essays. I think he’s the first person who ever told me I was a pretty good writer and encouraged me to take more writing courses.

The two teachers who made me think

I was raised in a military family and went to eight schools in 12 years. I had a lot of teachers, some good, some not. Mrs. Poole, Mrs. Perkins and Mr. Knudsen were among the good ones. The others will remain unnamed.

But if I had to pick just one teacher who was the most influential in my life, I would have to pick two: Bud Brewer and Stewart H. Price, who taught at Yokota High School, a Department of Defense school in Japan, where my father was stationed my junior and senior year.

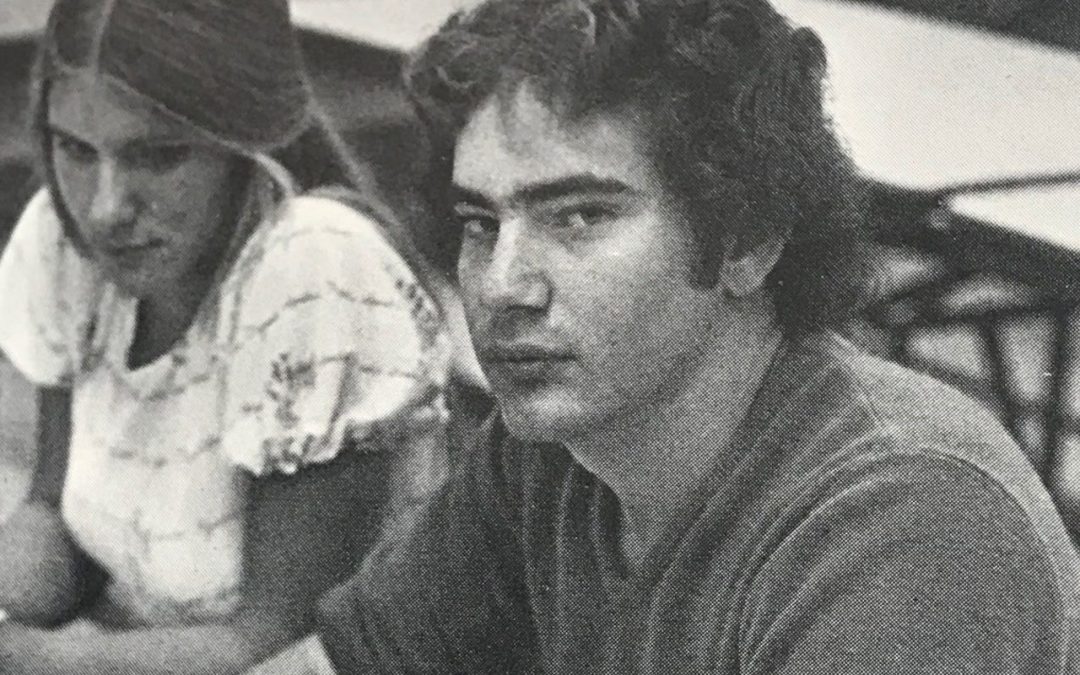

Brewer and Price were as different as could be. Brewer was a burly man with unkempt hair and an even more unkempt beard. So unkempt that it often held the remnants of his breakfast. He wore ill-fitting clothes that were hopelessly out of style, and like his beard, often bore residue from meals past.

Price was a small, wiry man who always dressed stylishly in turtleneck sweaters, flared slacks and polished shoes with big heels — stacks as we called them in the disco era. He had a neatly trimmed mustache and hip, wire-rimmed glasses.

Price taught English, and Brewer taught social studies, but the unlikely duo paired up to teach a class in humanities that you had to get special permission from your parents to take, not because they showed pictures of naked Greek statues and Rubenesque women in actual Rubens paintings, but because the class required students to do something we hadn’t really been required to do up to that point: Think critically and wrestle with ideas.

When they showed the first kouros statue on the screen, the snickers died quickly as they explained the Greek ideals of beauty, then transitioned to Plato, Socrates and Aristotle.

Art, architecture and literature became the vehicles through which traveled through time, and with each era, Brewer and Price would employ the Socratic method, pushing us to figure out for ourselves how everything was related and to develop our own theories on what it all meant. They challenged us to challenge ourselves not just about what we believed, but why we believed it. If you don’t challenge your own thinking, they reasoned, you won’t stand a chance when somebody else challenges it for you.

Watching the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral last month, I was taken back to the Brewer and Price lessons on how, beginning around the reign of Charlemagne, cathedrals were built to dwarf ordinary men, to impose upon them the majesty and the authority of the church. The innovation of flying buttresses, like those used at Notre Dame and Chartres, only allowed those edifices to soar higher toward heaven, a concept completely foreign to the ancient Greeks, who believed man is the measure of all things.

I took other courses from Brewer and Price. Shakespeare, poetry, drama, government and economics. I can’t think of a single one that didn’t challenge me. I still have my later edition of Paul Samuelson’s classic 1948 econ text, which I used during my MBA studies a few years back.

In my senior year, Brewer encouraged me to step way outside my comfort zone and try out for a role in the school play. I got a part, which was probably wasn’t surprising given that he was the drama coach.

That time I hitchhiked across Japan

Also during my senior year, Price helped me and several other students nurture an interest in Japanese history, religion, art and architecture. But to truly understand it, he said, you need to go to Kyoto, the ancient imperial capital, which was about a day’s drive from our base.

My buddy Dave and I decided to do just that over spring break. Unfortunately, we were both 17 and couldn’t legally drive off base. The Shinkansen “bullet” train was too expensive, and the slow train was too, well, slow. So we decided to hitchhike.

Our parents were dead set against it. It was the ’70s, and every parent’s head was filled with images of hitchhikers who were kidnapped into drug cults and murdered. My buddy and I tried every argument to no avail.

Then we enlisted Brewer and Price. They came over one night and showed my parents slides of the 700-year-old temples my friend and I had mapped out. They talked about what kind of learning opportunity it would be. They lauded Dave and me for our maturity, said we would soon be leaving the nest for college, and suggested it would be good to know that we’d had some practice fending for ourselves.

And they said that hitchhiking was perfectly safe in Japan. It wasn’t really practiced there, but most truckers knew what a kid beside the road with his thumb out meant because they’d seen it in American movies.

Dave and I had the time of our lives in Kyoto, though our parents would likely not have approved of the trip if they’d had advance warning of some of the details. Like when one of the truckers who picked us up couldn’t wait to show us how fast his truck could go on the expressway. Or when we waited until after dark to sneak into a temple that had a moon-viewing platform so we could gaze at the moon like 15th-century shoguns. Or when we met a cadre of Yakuza in a traditional Japanese bath and allowed them to take us out for a night of drinking afterward.

We not only lived to tell about it, but we also learned from what we’d lived. To say the trip was a launch pad for a lifetime of discovery and exploration is not an overstatement.

It’s sort of the nature of military brats to lose contact with the schools they attended overseas, particularly in the years before Facebook. I ran into Brewer a few years after college but never saw Price after I left Japan. We shared a few letters over the years, but they were few and far between. During the summer of 2012, my wife and I vacationed in Ft. Collins, Colo. I found out later from a classmate that Price had retired there. He died that November. Brewer died that same month.

I wish I could go back in time and let them know how much of difference each made in my life. But what I can tell you is this: If you are a teacher and you’ve affected just one kid the way Brewer and Price affected me, then you’ve made a difference.

Even if that kid never bothered to let you know.

John D’Anna is a reporter with the Arizona Republic and azcentral.com storytelling team. He is married to a first-grade teacher. Send story ideas or comments to [email protected] and follow him on Twitter @azgreenday.

Read or Share this story: https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-education/2019/05/06/teacher-appreciation-week-which-made-difference-my-life-yokota-high-school/1094241001/

[ad_2]

Source link