[ad_1]

Editor’s note: This story originally appeared in The Arizona Republic on April 3, 2013.

He was a teenager when he entered prison in 1972, a juvenile delinquent authorities called incorrigible. He was convicted of intentionally starting a fire on the fourth floor of the Pioneer Hotel, turning it into an inferno that killed 29 people.

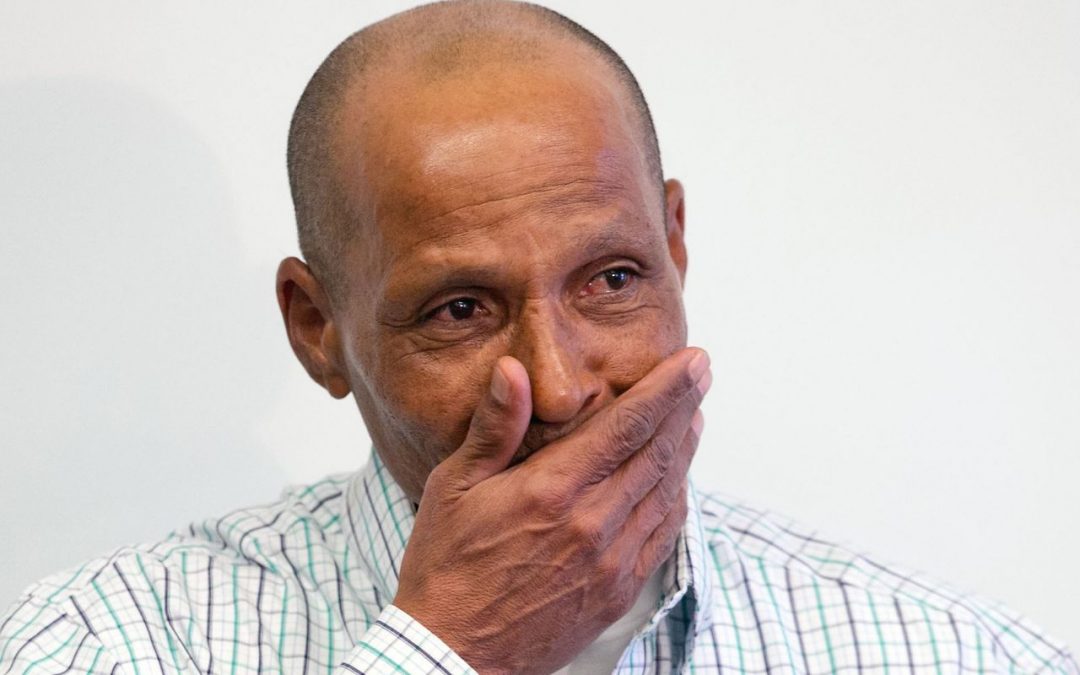

On Tuesday, Louis Taylor, now a 59-year-old man with a bald head and muscular arms, walked out of prison after serving more than 42 years behind bars for murder. Taylor won his freedom, if not his exoneration.

During a hearing called in light of new questions about whether the fire had been caused by arson, prosecutors chose not to pursue a new trial, and Taylor chose not to risk one.

Instead, he spoke the words “no contest” 28 times, once for each time a Pima County Superior Court judge read a charge of murder, listing the name of each victim in what became a roll call for what has been called the deadliest disaster in Tucson’s history. After the pleas, Judge Richard Fields sentenced Taylor to the time he had served and ordered that he be released.

Outside the gates of the Arizona State Prison Complex-Tucson, just before 3 p.m., Taylor said, “It feels good just to feel Mother Earth underneath my feet, free Mother Earth.”

Taylor said the full story of the December 1970 fire had not been told or understood. “It’s two tragedies,” he said, “the Pioneer Hotel fire and me getting convicted for it.”

Volunteer attorneys with the Arizona Justice Project had raised doubts about the evidence, asking a Pima County Superior Court judge to vacate the original convictions and consider trying Taylor again in light of the new evidence.

County Attorney Barbara LaWall said that much of the evidence in the 42-year-old case had been destroyed and that many witnesses had died.

But in a news conference after the hearing, she said she had no doubts about what happened at the hotel, even if the case could not go to trial now.

“A fire was willfully and deliberately set, and Louis Taylor was the person who did that,” she said.

Despite the passage of time, Taylor’s case unearthed strong emotions — memories of a fire that claimed whole families, racially charged controversy over the evidence and a dramatic hearing in which victims faced the man who was about to be set free.

Paul d’Hedouville was 4 when his father died in the fire. In court Tuesday, he gave Taylor parting words of advice.

“Do as you choose, Mr. Taylor,” he said, “but choose wisely and do not waste your new beginning of life.”

MORE: Man behind bars 42 years in hotel fire adjusts to freedom

A Tucson tragedy

The fire started on the fourth floor of the hotel on a December evening. From there, it raced up the open stairways, which acted like chimneys, said Al Pesqueira, a Northwest Fire/Rescue District assistant chief who co-produced a documentary about the blaze.

Rescue efforts were hampered because the Fire Department’s tallest ladders could only reach the ninth floor of the 11-story hotel.

Most of those killed in the fire were found in the hotel’s hallways or in their rooms, dead of burns and smoke inhalation. Among the dead were the hotel’s owners, who had been assured by the front desk that the fire was under control. Some people leaped to their deaths from their room windows.

Two families, one of five and one of six, were among the dead. In one case, Pesqueira said, it appeared the parents had thrown mattresses to the sidewalk and then tossed the children down in an attempt to save them. The parents were found inside the room, he said, possibly after realizing their attempt was futile.

Taylor was taken into custody after the fire, according to his attorneys, because a hotel employee reported seeing a suspicious African-American youth at the hotel and Taylor could not give police a good reason why he was at the hotel. He was questioned for six hours, then arrested on juvenile charges of trespassing.

Taylor was known by police to frequent the downtown Tucson area. The grade-school dropout had been committed four times to juvenile halls for various crimes, including strong-arm robbery at age 13.

According to a 1970 story in the Tucson Daily Citizen, Taylor was called “utterly incorrigible” by a reform-school superintendent.

He was charged with 28 counts of murder. One of the victims, a nurse, died of smoke inhalation months after the fire, but Taylor was never charged with her death.

The trial was moved to Phoenix because a judge decided Taylor could not get a fair trial in the city that had just lost many of its prominent citizens and a downtown landmark.

At Taylor’s 1972 trial, the custodian of the hotel testified that the teenager acted heroically during the early-morning fire, helping him try to extinguish it, according to a story from the Arizona Daily Star. The hotel’s beverage manager testified that Taylor helped him carry injured guests to safety, another story said.

Taylor testified on his own behalf, proclaiming his innocence. “All that I was doing was helping,” he testified.

After a jury found him guilty, the trial judge told a reporter: “The evidence supports a conviction, but I would not have convicted him myself.”

New questions arise

Taylor, who entered prison on March 30, 1972, was far from a model inmate. His prison record shows 26 major infractions, including narcotics possession, stealing, fighting and arson. In September, he was moved from medium to maximum security, prison records show.

Taylor’s case was featured nationally on “60 Minutes” on Sunday. The CBS newsmagazine had raised questions about his case in a story that aired in 2002. That story attracted the attention of the Arizona Justice Project, whose volunteer attorneys have worked since to free Taylor.

Part of the work focused on advances in fire science since the 1970s. “By today’s standards, there is no evidence that arson caused the Pioneer Hotel fire,” Taylor’s attorneys wrote in a court motion.

In November, attorney Edward Novak, an attorney who volunteered his time to the Justice Project, questioned Cyrillis Holmes, a fire expert from California who initially testified the fire was arson, set in two spots along a fourth-floor hallway. In a sworn deposition, Holmes told Novak that when he met with Tucson officials, he said their suspect was likely an African-American who was 18. That meeting was the first day of Holmes’ investigation, days after Taylor’s arrest.

Holmes testified he determined this because, “Blacks, at that point, their background was the use of fire for beneficial purposes.”

Holmes said arson fit the profile of Black youths of that era. “If they get mad at somebody, the first thing they do is use something they’re comfortable with,” he testified. “Fire was one of them.”

Holmes, reached last week at his California home, said he stood by his profiling of the potential suspect. He also stood by the science of his methods, saying that even using today’s fire-science methods, he would have determined arson.

Attorneys for Taylor said in a motion that Holmes’ methods were faulty. They also introduced their own expert evidence that questioned whether the fire could be conclusively called arson.

Marshall Smyth, who investigated the fire for an insurance company the afternoon after it started, originally ruled the fire was intentionally set at one spot along a fourth-floor hallway. But he re-examined the case and testified last year that he could no longer say it was arson.

Smyth, in a phone interview, said fire investigators at the time had no real science behind their methods.

“It was all guesswork,” he said.

Fire investigators didn’t understand the concept of “flashover” fires until the early 1990s, Smyth said.

Those fires occur when gases catch fire and engulf a room. Before that concept was understood, many fires were mistakenly labeled as arson, he said.

Memories and questions

The plea of “no contest” allowed Taylor to maintain his innocence, attorney Novak told the judge Tuesday. But Taylor did not take that opportunity, preferring not to speak in court.

In the hearing, d’Hedouville, the young son of one of the victims, said he did not want those who died to simply be a list of names.

“Those 29 souls are inexorably linked together by history,” he told the court. “May their souls rest in peace.”

D’Hedouville said his father had expected his family to celebrate Christmas at the Pioneer and had presents in his suite.

His father ended up being buried on Christmas Eve, his son said. He woke up Christmas morning asking his mother who would play Santa Claus since his father was gone.

On Tuesday, d’Hedouville wore a tie clip of the scales of justice worn by his father, who had just made partner in a law firm when he died.

“I harbor no feelings of ill will or vengeance against you,” he said from the witness stand, addressing Taylor directly.

When d’Hedouville returned to his seat after making his statement, his hand visibly shook as he drank from a bottle of water.

He and his wife, and relatives of two other victims, were set to tour the Pioneer Hotel building, which has retained the name but has been turned into an office building, a facade covering the original charred walls.

There did not appear to be any family members of Taylor’s in the courtroom or waiting for him when he was released from prison hours later.

Michael Fierro, 29, who served prison time with Taylor, stood in the gallery of spectators at the hearing, grimacing to hold back tears.

Fierro said that Taylor was well-respected in prison and that he was glad to see him set free.

“He said he would show his innocence one way or another,” Fierro said. “He had it deep down that he was innocent.”

Fierro said Taylor did not have any family he knew of.

He only kept contact with a handful of friends whom he met in prison, Fierro said.

LaWall, the Pima County attorney, said Tuesday that comments by Holmes, the fire expert, might have hurt the prosecution’s case in court.

David Smith, who runs a fire-investigation business in Bisbee and is a city councilman there, said when re-examining old blazes, no one can pinpoint an exact cause.

“There’s not enough data to be able to say what it was,” Smith said in an interview Monday. “You can just say there’s no way in hell they reached the conclusion they did.”

Smith was a policeman during the Pioneer Hotel fire but switched careers after becoming intrigued with fire science.

As a juvenile detective in 1970, he questioned Taylor the night of the fire, which left him feeling conflicted about Tuesday’s release.

He knows that the science isn’t there to conclusively prove arson, he said, but the police officer in him was still suspicious of the 16-year-old he questioned hours after the fire.

One oddity still stands out more than 42 later, Smith said — a point that was key to prosecutors’ arguments at trial. Officers were strip-searching Taylor that night and searching his clothes.

“(Taylor) reached in front of his jockey shorts and pulled out five books of matches,” Smith said, “and handed them to me and smiled at me.”

KVOA in Tucson contributed to this article.

Read or Share this story: http://azc.cc/2v1uYMZ

[ad_2]

Source link