[ad_1]

Some parents are criticizing the Chandler Unified School District for showing a movie with the “N-word” to junior high students.

Wochit

The decision to show a movie about slavery and the Underground Railroad that uses an iteration of the N-word to junior high students has some Chandler parents concerned.

A Chandler Unified School District spokesman said “A Race to Freedom” has been shown in the district for years and does not use the N-word.

But that’s open to interpretation.

The movie site IMDB’s parental guide for the film states the N-word “is used throughout the movie. Although it is pronounced by many in the film: ‘niggre.’ “

However it’s pronounced, it was too much for parent Amber Hutchinson, whose child attends Santan Junior High School.

“I don’t care how you say it. That word hurts,” Hutchinson said. “You’re referring to an African-American person in a very demeaning and disrespectful manner.”

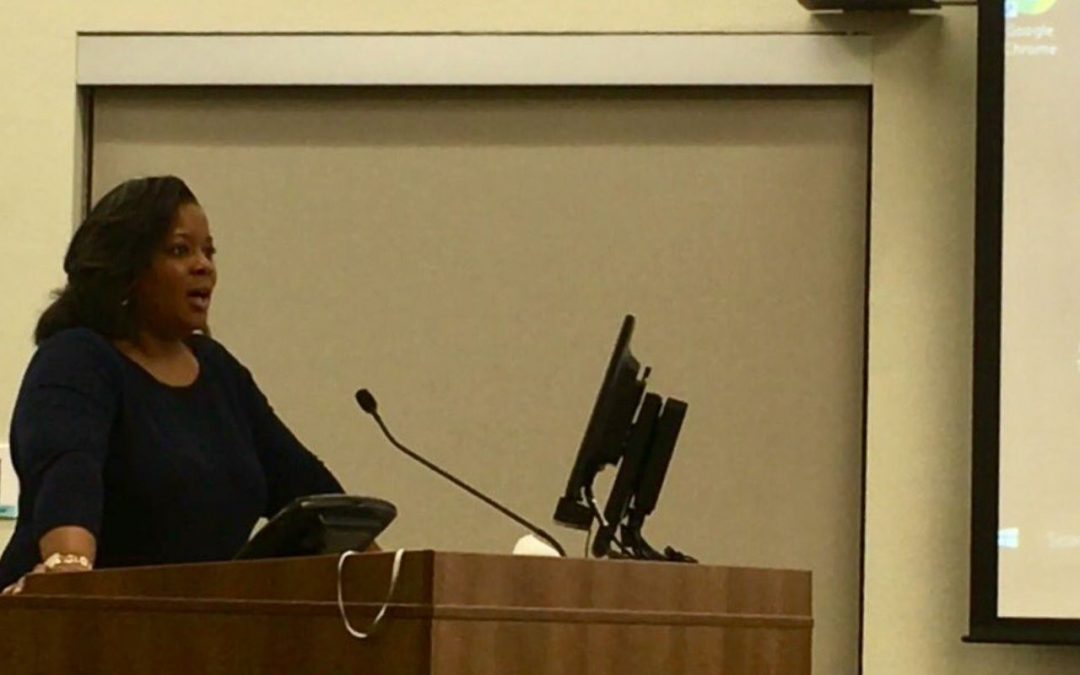

Hutchinson first voiced concern on social media, and was joined by several members of the Chandler-based Black Mothers Forum when she spoke to district leaders at a school board meeting on Sept. 13.

“CUSD employees are responsible for providing a safe, productive environment for students and adults engaging in equal learning,” Hutchinson told the board. “You failed. You failed me. You failed my child.”

Robert Rice, president of the governing board, told The Arizona Republic after the meeting that public reviews of curriculum take place whenever new material is introduced, but that not every movie is accounted for.

“We just always need to be sensitive to other cultures, races,” Rice said. “I have blind sides. We all do. I think that’s when we can have other groups help us understand where we’re missing those sensitivities.”

Raising awareness

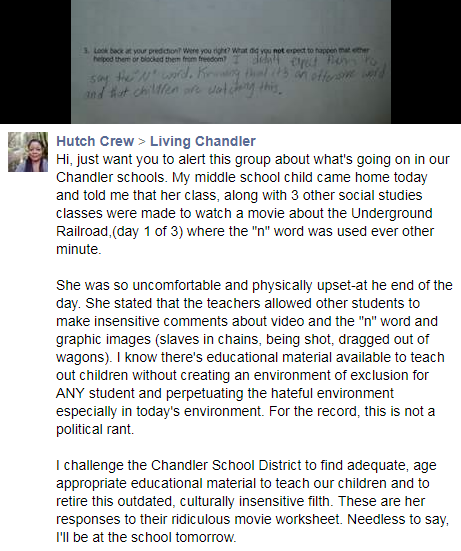

In Hutchinson’s original Facebook post, she decried Chandler’s choice to show the film, which was released in 1994.

“I challenge the Chandler School District to find adequate, age appropriate educational material to teach our children and to retire this outdated, culturally insensitive filth,” the mother said.

Hutchinson’s post was met with support from some and criticism from others. Some suggested she should reach out to school leaders instead of posting online and others said historical context and accuracy is important in teaching students about slavery.

At the board meeting, board members did not respond directly to her comments, which is standard practice during the public comments portion of the meetings.

At the end of the meeting, Superintendent Camille Casteel thanked Hutchinson and parents who addressed the board on other issues, saying, “We know we’re not perfect. We’re trying. There’s a lot of lives and dispositions and attitudes to try to manage and shape, but we’re working real hard to do that.”

A district spokesman noted that the Dove Foundation, a non-profit organization “whose mission is to encourage and promote wholesome family entertainment,” approved of the film to be shown to individuals 12 years old and older.

The foundation describes the film, which focuses on four slaves’ journey to freedom from North Carolina to Canada, as “powerful” and credits its themes of perseverance as being family-friendly.

Hutchinson disagreed.

“As long as someone is giving breath to it, it’s going to remain alive,” Hutchinson said of the N-word.

Words matter

Neal Lester, an ASU Foundation Professor of English and the founding director of the Project Humanities initiative, has taught an entire course on the N-word.

He said the inability to see nuance or understand the pain certain words can cause certain students is why these situations keep manifesting in schools.

“There are ways you can teach the Underground Railroad without dramatizing it,” Lester said. “These are not college students. You have to prepare young people for discussion. One person may be disarmed by something so racially charged.”

Black students make up 5 percent of the district’s total enrollment, according to the district. Hutchinson says her daughter can feel uncomfortable with lessons that aren’t sensitive to minorities.

Hutchinson has raised concerns in the past, including after a lesson in which her daughter and classmates were asked to read slave dialect aloud from the 1969 novel, “The Cay.”

“I think that the school district is being very lazy about updating their curriculum,” Hutchinson said. “I don’t think that they have a sense of awareness about who their clientele is and who they’re speaking to. They’re not serving their population.”

Lester advocates for showing documentaries instead of dramatizations to illustrate the realities of slavery, as well as initiating extensive discussions with students ahead of time to prepare them for the content.

“If you’re trying to make a point about dialect, bring in an audio version,” he said. “Tailor the lesson so it’s not coming out of the discomfort of a student’s mouth. There’s a lot of work you can do to prepare students without articulating the word and saying it out loud.”

If a student or parent feels uncomfortable and would like to opt out of a lesson or tackle an alternative lesson, they should be given that right, he says.

“You have to recognize the sensitivity of language, whether its homophobic language, sexist language, or ableist language,” Lester said. “Words matter.”

How to move forward

This is hardly the first school, movie or book that has raised difficult questions for schools.

Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” uses the N-word more than 200 times. In 2011, a publisher inserted the word “slave” in its place in an attempt to avoid the American classic being dropped from school reading lists.

The 1977 ABC mini-series “Roots,” which uses the N-word as it explores the horrors of slavery, ranks as one of the nation’s most-watched telecasts and has also been shown in schools. The 2016 remake continued to use the racial slur for authenticity.

“You can’t get around the history of the word,” Lester said.

But it should be approached carefully.

“Even if the spelling and pronunciation are different, educators need to ask themselves: How might our best intentions go awry? Parents have to be brought in about these sensitive issues,” he said.

Hutchinson questions why the school did not consult parents about the film’s content before showing it in class.

At the beginning of each school year, the district sends home a list with the rating of each film that is to be shown throughout the year. The list does not discuss the content of each film.

Hutchinson would like to see greater outreach in navigating such sensitive topics.

“They could have sent a letter home to the parents and said, ‘This is a great opportunity to talk to your children about the material in this film so that they understand the scope,'” she said. “You took that opportunity away from me.”

READ MORE:

Is it ‘just a word’? Questions, comments about the N-word controversy at Desert Vista

Read or Share this story: http://azc.cc/2x2aRzI

[ad_2]

Source link