[ad_1]

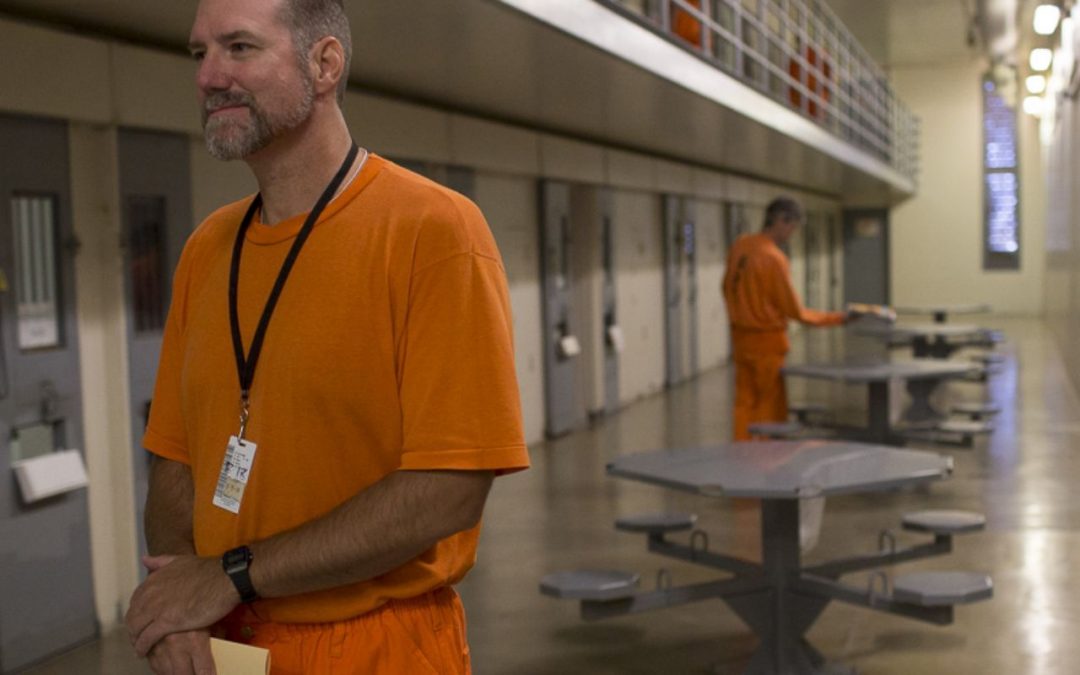

A tour of Arizona’s new death-row facility in Florence. Thomas Hawthorne/azcentral.com

The first time in 20 years that Richard Greenway was let out of his prison cell without shackles, he didn’t know what to do with his hands.

Greenway, 49, has been on Arizona’s death row since 1989. He was sentenced to death for the 1988 murders of a woman and her daughter during a burglary in Tucson. From 1997 until last summer, like all other death-row prisoners, he was in the maximum-security Browning Unit, at the Eyman Prison in Florence.

There, he spent 23 hours a day in a 9-and-a-half-by-10-foot concrete cell with a perforated steel door, a bench bed, and sink attached to a seatless toilet. He could take no educational courses, have no job or face-to-face visitors, and the only human contact he had for those 20 years was when correctional officers came to his cell, cuffed his hands behind his back, searched his most private body parts for contraband and led him to the showers or the equally small exercise cell.

But that kind of isolation takes its toll on prisoners and corrections staff alike. State prison systems, recognizing the crippling psychological effects — and bowing to federal lawsuits alleging cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment — have begun moving away from it.

“It’s hard to explain the deprivation,” Greenway told The Arizona Republic in a face-to-face interview on the day before Thanksgiving. “It weighs on your mind.”

“I had no physical contact with anyone except for the officers who would handcuff me,” he said.

Greenway marveled at the fact that he could meet with a reporter.

“We’re sitting across from each other,” he said. “We shook hands.”

‘Chow in 30 minutes’

Arizona had been planning the change for years. A federal lawsuit settled in March sealed the deal, and in June, the Arizona Department of Corrections started moving all but 27 of its 120 death-row prisoners to the Central Unit in Florence, where they have cells that open, and where they can go out on prison recreational fields for several hours a day, play basketball and volleyball or just walk, where they can socialize freely in cell-block common areas and take meals with each other instead of alone in cells.

But the first time after the move that the correctional officers said, “Chow in 30 minutes,” Greenway assumed that they would deliver meals to the cells. Instead, he and others were let out of their cells, allowed to line up and walk, unshackled to the nearby mess hall, where for the first time in 20 years or in all of their imprisonment, they sat down to eat with other human beings.

They are also now allowed to have contact visits with their families and attorneys, instead of over the phone or through glass.

So far, prisoners, wardens and defense attorneys alike are pleased with the change.

“They’re all a lot happier,” Assistant Arizona Attorney General Michael Gottfried said at a recent meeting of the Capital Case Oversight Committee, a regularly meeting advisory body to the Arizona Supreme Court made up of judges, defense attorneys and prosecutors.

Gottfried noted that there was little conflict among the prisoners.

At that meeting, Assistant Federal Public Defender Jennifer Garcia added that Corrections staff had been “very, very nice” in accommodating the new face-to-face meetings between prisoners and their lawyers.

A different kind of prisoner

The prisoners who remain in Browning are the hard-core gangsters, the seriously mentally ill, and some disabled prisoners. The Central Unit does not yet meet Americans With Disabilities Act standards — the cell doors are not wide enough to accommodate modern wheelchairs — but that is a task for down the road. The state’s three female death-row inhabitants have been moved into the general population at the Perryville prison near Buckeye.

The men in Central Unit are housed in three different tiers, which is what they call a unit of cells. They are stacked in two runs, or levels, of about 20 cells that open onto a common area where prisoners can chat or play board games when they are not locked in their cells. The mess hall and visitation area are nearby.

Out on the recreation grounds, a dirt expanse the size of a football field, prisoners play basketball, pushing and taunting with trash talk. Others walk around the perimeter in pairs. Still others sit at pay phones along one end.

As a group, they seem larger than average men, lean from eating prison food, and many have that loping walk of athletes, rather than the exaggerated rooster strut — arms swinging way farther than normal behind the back with each step — of the men in general population.

As the death-row denizens head back to their tier, and the general population streams out to the field, Gerald Thompson, the prison warden, remarks that he feels safer among the death-row men than among the career criminals and gangsters in the general population.

They are kept separate because they are different sorts of prisoners.

“Their issues are on the outside, which is what got them onto death row,” said Carson McWilliams, the division director for the Corrections Department. He is a 39-year veteran of the institution.

The men and women on death row are all convicted murderers, but they are not usually repeat criminals. They tend not to be members of the prison gangs.

“Historically, death row has never been a group that displays racial lines,” McWilliams said.

And yet they were charged with and convicted of committing the worst crimes in the book, those punishable by death.

Debra Milke, for example, was convicted of engaging two men to kill her 4-year-old son, though the conviction later was thrown out because of police and prosecutor misconduct. She was freed.

Nonetheless, Milke spent 24 years in custody, most of it as a death-row prisoner — except there are so few women sentenced to death that there is no designated death row for them.

Instead, she was placed in the maximum-custody unit of a women’s prison. And though she had been convicted of the worst crime in the prison, she was a working-class woman from Phoenix, and she told The Republic she was terrified by female gang members and hardened criminals in that unit.

When Milke got out, she was terrified by the expanse of freedom. She had to adjust to being outside, stepping a few feet farther from the door each night until she felt safe enough to venture down the block.

Conversely, a man who had spent 20 years on Nevada’s death row before being exonerated and released earlier this year was calm and collected. When asked why he wasn’t insane, part of the answer was his religious faith. But the other part was that he was in a prison where death-row prisoners had jobs and visits and regular human contact with each other.

Lights kept on 24 hours a day

In the early to mid-1990s, Arizona, like many other states, was in the throes of “tough-on-crime” politics that resulted in harsh punishing regimes for criminals. Parole was abolished, replaced by community supervision. Then-Gov. Fife Symington encouraged chain-gang work by death-row inmates. They were put to hard labor on garden plots inside the prison grounds.

In 1997, a woman who had married a death-row prisoner while he was incarcerated tried to free him one day as he worked on a chain gang near a fence at the Florence prison. She fired an automatic weapon at guards, and when her husband ran for the fence, he was wounded by bullets fired in response by correctional officers. He then asked the wife to shoot him and finish him off, which she did before she was cut down in a hail of fire from prison staff.

Shortly afterward, the death-row prisoners were moved into maximum security and there they stayed for the next 20 years.

Arizona corrections officials balk at the term “solitary confinement,” but in 2015, the United Nations approved guidelines on imprisonment referred to as “Nelson Mandela Rules.” The guidelines describe solitary as “confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.” That fit the description in Arizona.

Arizona death-row prisoners got two hours of exercise in a confined area three times a week and three showers a week. Their meals were delivered to them through a slot in a corrugated steel door. And if they communicated with each other, it was through the wall, sometimes tapping in code, and by “fishing,” that is, passing notes and reading materials, coffee packs and other things using strings they had made by unraveling cloth.

The lights were kept on 24 hours a day.

Correctional Officer Frank Reynolds works among the close-custody death-row inmates and can contrast today’s situation with when they were all housed in Browning.

“They didn’t really have any reason to come out of their cells,” he told The Republic.

And when they did, he said, “It was more like a caged animal in a zoo. They were confused.”

Director McWilliams notes that the close custody is safer and more economical.

“If you can keep the inmates actively involved in something, whether sports or work, it’s positive,” he said.

The men are more socialized. They have “some way to express themselves rather than being in a cell and angry all the time.”

Managing them requires fewer correctional officers. Officers no longer have to deal with inmates one by one, or deliver meals to 120 cells. And being able to deny privileges gives the wardens a tool to control inmates. Defy orders, lose privileges.

McWilliams has stated in court documents that Corrections began planning the move to close custody in 2015. It was being experimented with in other states with positive results.

That same year, the department was sued by attorneys affiliated with the Arizona Capital Representation Project on behalf of a death-row inmate named Scott Nordstrom.

The lawsuit, which was filed in U.S. District Court in Phoenix, alleged that the manner in which the agency confined death-row denizens violated the 14th Amendment right to due process, and the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

It was settled in March 2017, finalized in August, though the prisoners had already been moved by then. The attorneys for the suit declined comment for this story because they are still suing the state of Arizona and the Department of Corrections for attorneys’ fees.

The state is balking at paying their demand for nearly $150,000, maintaining that they were already working on changing the system.

Unshackled, ready for recreation

Back on Richard Greenway’s tier, prisoners began returning from the recreation field while he and a reporter were still seated at a table in the tier’s common area. The cell doors clanged suddenly open, and those inmates who had not taken recreation came out and looked on,some of them from the upper run.

They gathered in groups near the doors, as many as 20 convicted and condemned murderers, unshackled, surrounding Greenway and his visitor.

Brian Dann, who was sentenced to death for killing three people in Phoenix in 1999, came out of his cell to share some literal gallows humor.

It was the day before Thanksgiving, and he knew Greenway was talking to a newspaper reporter.

“I heard President Trump was pardoning some turkeys, and I thought they meant Richard,” Dann said.

Then he offered a tour of his cell. It was longer and narrower than the cells in Browning. It had a window to the outside on the far end of the cell.

On the other end of the cell, above the door into the common area, he had posted a small sign.

“Due to recent budget cuts, the light at the end of the tunnel has been turned off,” it said.

READ MORE:

The long journey from death row to freedom: AZ lawyer’s sleuthing frees convict

Death-row inmate turned prisoner advocate: ‘Hate the crime but still love the person’

Former death-row inmates talk about ‘Life After’

Read or Share this story: http://azc.cc/2AYLtvD

[ad_2]

Source link