[ad_1]

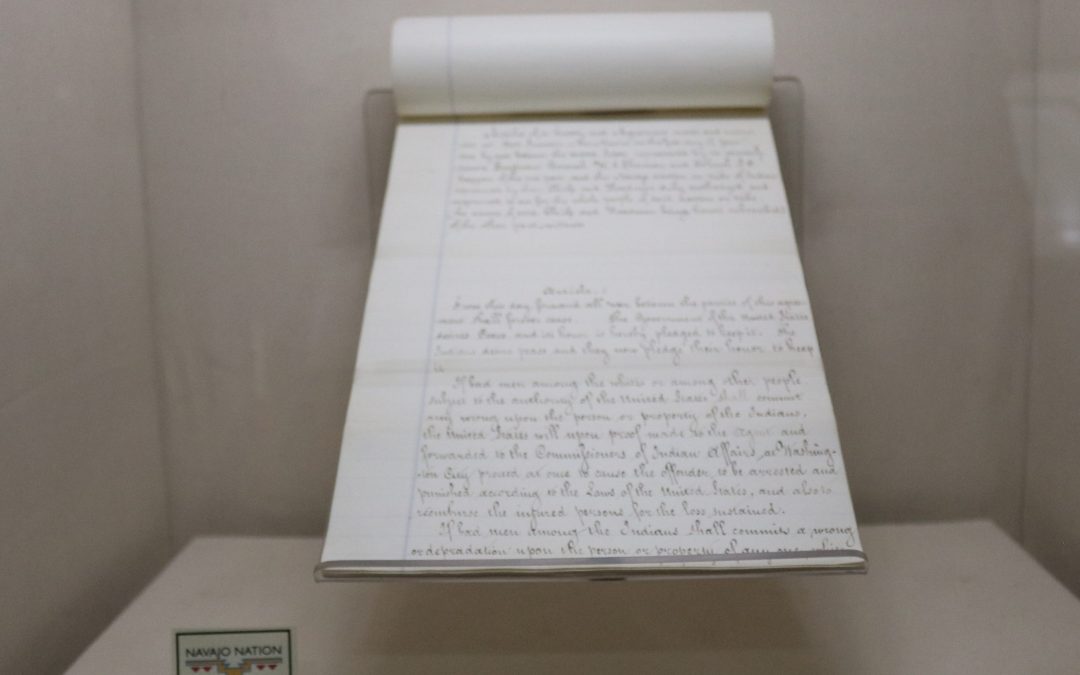

A copy of the 1868 treaty that brought the Navajo people back to their homeland, after years of imprisonment, has been donated to the Navajo Nation.

In 1863, the federal government evicted nearly 10,000 Navajos from their ancestral homeland and force-marched them 300 miles east, finally imprisoning them near the village of Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico. It’s known as the Long Walk.

On June 1, 1868, Navajo leaders and the U.S. government signed the treaty of Bosque Redondo, which ended the Navajo people’s imprisonment, allowing them to return home.

The Navajo Nation recently accepted one of three known copies of the treaty, and it will be on display starting June 1. The recently donated copy was given to Indian Peace Commissioner Samuel F. Tappan because he assisted in the treaty’s negotiation process.

Today, the treaty has 17 lined pages, each approximately 8-by-12 inches, tied with a faded red ribbon. Small tears on the cover pages were stabilized last spring by the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, Massachusetts. Documents indicate since it is the peace commission’s copy, it was not signed by Tappan or by Lt. Gen. William T. Sherman. Markings for the Navajo leaders were printed by a clerk.

It does have the signature of Delgadito, the only Navajo leader who could write his name.

A July 2018 appraisal listed it in “very good condition” with a market value of $10,000.

The original treaty was presented to President Andrew Johnson and is kept in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. Another copy was presented to the Navajo Nation, but its whereabouts are unknown.

Tappan acted as secretary during the proceeding from May 28 to June 1 in 1868 when the treaty was signed at Fort Sumner, according to the Navajo Nation Museum. As part of the process, he hired three clerks to produce the copies.

Tappan’s version of the treaty was discovered last year by his great-grandniece Clare “Kitty” Weaver and she donated the item to the Navajo Nation Museum after finding it in the attic of her home in Manchester, Massachusetts.

“This is a historic event for all Navajo people,” said Navajo Nation Museum Director Manuelito Wheeler Jr., the treaty will be held at the museum. “We’re very honored and proud that our tribal museum is capable of those types of standards that are the same as the national archives.”

There are 573 federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States, but not all have treaties with the U.S.

Thank you! You’re almost signed up for

Keep an eye out for an email to confirm your newsletter registration.

According to the National Congress of American Indians, 370 treaties were ratified between 1778 and 1871, the year treaty-making ended.

From Massachusetts to the Navajo Nation

Weaver made the decision to donate the Tappan copy of the treaty to the museum after her visit to the Fort Sumner Historic Site and Bosque Redondo Memorial in New Mexico. The Tappan treaty was on display as part of the 150th anniversary installation at the site in June 2018.

Before she went to Fort Sumner, Weaver said she understood there was history behind the treaty, but not its importance. The actions of one Navajo woman made Weaver fully understand the significance of the treaty. During the installation, Weaver noticed a Navajo woman walk quietly up to the treaty case, standing with with her head back.

The New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs identified the woman as Navajo quilter Susan Hudson.

“She then put something at the base of the treaty,” Weaver said.

It was yellow corn pollen (tádídíín in Navajo), which is still visible in the left corner of the former treaty case. Corn pollen is a means of communicating with the Navajo Holy People and represents safety and happiness. After she placed the item, Hudson asked to meet the person brought the treaty to the installation.

Weaver identified herself. They ended up hugging and crying, though no words were spoken.

“I can not tell you what that woman did for me,” Weaver said. “That was a significant moment when the treaty became not just a historical document. It became a living being. Not only for you all but for me.”

By the winter of 2018, Weaver had decided to donate the treaty to the Navajo Nation, working with the Navajo Nation, New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs and the National Archives to safely transport the treaty to the Navajo Nation Museum.

“If (Tappan) were here today, he would be so proud of everything that happened,” Weaver said. “I think he saved that treaty up in that attic for today.”

Treaty on exhibit until June 8

Weaver signed the donation form of the treaty to the Navajo Nation Museum on May 14, but before the treaty could be officially accepted by the museum, the tribe had to formally accept it.

Navajo law states donations to the Navajo Nation exceeding $1,000 must be approved by the Naa’bik’íyáti’ Committee of the Navajo Nation Council. The treaty is valued at $10,000.

On May 16, a bill was introduced by Navajo Nation Council Delegates Otto Tso and Herman Daniels to formally accept the donation. The legislation passed through the Naa’bik’íyáti’ Committee on May 28, passing 17-0.

To commemorate the 151st anniversary of the treaty’s signing, the Navajo Nation Museum will have the treaty on exhibit from June 1 to June 8. Afterward, it will be securely stored and protected in the museum vault.

Wheeler hopes to eventually have the treaty travel across the Navajo Nation, displayed to different schools, chapters houses, and communities so Navajo people can see it.

“People just don’t go to museums unless we have something like this,” he said.

The idea is to put the treaty in cases suitable for traveling, Wheeler said. These cases will need to maintain the humidity, temperature, and correct light for the treaty.

In 2018, the original Treaty of 1868 was on loan to the museum from the National Archives and on display at museum for the entire month of June. Wheeler said between 30,000 to 50,000 people came to see it.

Leaders praise the donation of the treaty

Several leaders on the Navajo Nation celebrated the donation to the Navajo Nation Museum to celebrate on May 29.

It’s been 151 years since the Treaty of 1868 was signed, and Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez said those years are significant because it shows the rebuilding of a nation.

Nez publicly thanked Clare “Kitty” Weaver during a press conference unveiling the treaty at the Navajo Nation Museum on May 29 for donating a piece of U.S. history.

“We are the most influential Indigenous nations in the world because of what happened during that time,” Nez said, indicating Navajo ancestors did not give up.

“The resilience should be magnified,” he added. “It is our turn to look at the next 150 years for our nation.”

Navajo Nation Speaker Seth Damon was also in attendance.

“We as Navajo people have a piece of history that has not only burdened our people but has given life, strength and hope to our people,” he said. “We came back to the four sacred mountains and it’s because of our ancestors that signed that document. It’s because of those individuals that fought and bled for us to come back.”

The Navajo Nation may be one of the few tribes in the country that has a piece of their own history back on their reservation, Damon said.

“You gave that back to the Navajo people, that’s something that’s going to be remembered forever,” Damon said to Weaver.

Farmington Daily Times reporter Noel Lyn Smith contributed to this article.

Reporter Shondiin Silversmith covers Indigenous people and communities in Arizona. Reach her at [email protected] and follow her Twitter @DiinSilversmith.

Support local journalism.Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

Read or Share this story: https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona/2019/05/30/copy-1868-treaty-returns-navajo-nation/1278298001/

[ad_2]

Source link