[ad_1]

After two years of intense scrutiny from the U.S. Senate and elsewhere, online ad-posting site Backpage.com announced that it is shuttering its adult services section, which was repeatedly accused by critics of facilitating child prostitution and human trafficking.

USA TODAY

A federal grand jury in Phoenix is hearing evidence against Michael Lacey and James Larkin, the founders of the controversial classified-ad website Backpage.com. Lawyers for the two men acknowledged in a recent court filing that “indictments may issue anytime.”

Such an indictment would be the first federal criminal charges against the men, amid increasing allegations that the website knowingly accepted ads offering sex with underage girls.

But even as their legal problems have grown, the two men who started the Phoenix New Times in 1970 have become local philanthropists and political donors to Democrats in Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado.

All told, the two men have made federal and state political contributions of $162,200 since 2013 — $60,200 of that to Arizona politicians and political committees, and $10,600 of that to U.S. Rep. Kyrsten Sinema in 2013 and 2016, according to an analysis of state and federal campaign-finance records. She was the biggest individual beneficiary of their donations in Arizona.

Federal campaign-finance records show Sinema received an additional $10,800 in donations from the spouses of two other Backpage executives on the same day in 2016 when Lacey donated $5,400 to her. Those executives, Scott Spear and John Brunst, and their spouses have made federal contributions of $195,700 since 2013, $29,700 of that to Arizona politicians. The donations from Spear and Brunst mirror many of those made by Lacey and Larkin.

Sinema’s office repeatedly refused to answer any questions about the donations.

$40,000 to Arizona Democratic Party

The Arizona Democratic Party took $40,000 from the two men last year, three months before they faced their first criminal charges in California. Asked if the party intended to keep the $40,000, a spokesman, Enrique Gutiérrez, said the money had already been spent.

The Frontera Fund, which the two men started in 2014, says it has donated money to 22 charities listed on its website, most of which support immigrants’ rights.

In 2007, then-Sheriff Joe Arpaio had both men arrested; they were accused of revealing grand-jury information. They sued the county over the arrests. The $3.75 million settlement created the groundwork to launch the fund.

The fund doesn’t state the amount of its donations today. Officials at several of the organizations said they were not aware of the alleged facilitation of sex trafficking through Backpage. Just one of the organizations that responded, the Si Se Puede Foundation, said it would cease accepting donations.

Larkin and Lacey, along with their business partners, have been besieged by a growing number of legal difficulties: Criminal charges in California; lawsuits by trafficking victims in six states; and a blistering report in January by the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. That report concluded that Backpage knowingly accepted ads from pimps who had coerced underage children into having sex for money.

READ MORE: Senate: Backpage.com ‘knowingly concealed evidence’

Some who have tracked the Backpage controversy find it abhorrent that politicians or even charities would accept donations from the two. “Once you have knowledge of Backpage’s involvement, and you read the Senate report, can you accept any donations from the principals of Backpage in good conscience?” asked Mary Mazzio, whose documentary “I Am Jane Doe” tracks the cases of young girls who were prostituted on the website.

The existence of the secret federal grand-jury investigation in Phoenix was disclosed by Lacey and Larkin’s attorneys in a motion filed in February in a civil lawsuit against them in Washington state, urging the judge to put a temporary halt to any further legal proceedings. “For example,’’ the lawyers wrote, “the United States Attorney’s Office of the District of Arizona is currently conducting a grand jury investigation of Backpage.com, and indictments may issue anytime.” The judge in that case granted the motion.

Asked about a grand-jury investigation, a spokesman from the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Arizona, Cosme Lopez, said, “I can’t confirm or deny” that such an investigation exists.

Attempts to reach Lacey and Larkin were unavailing. One of their attorneys, Daniel J. Quigley, said he would pass along a reporter’s phone number. Neither man called.

Known for provocative journalism

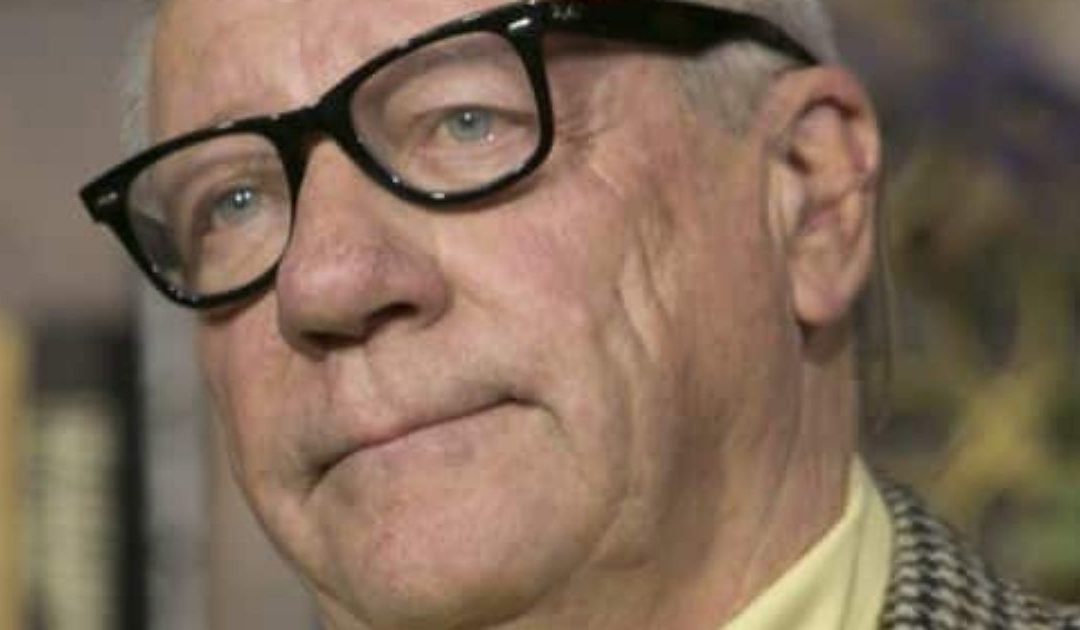

For Lacey and Larkin, the two counterculture journalists who started the New Times on a shoestring budget in 1970, the multiple civil and criminal charges represent a sea change. The two men who were known for provocative journalism are now ensnared in legal troubles over enormous profits they have made from an advertising site.

The New Times empire was once highly profitable, so much so that the two men bought 16 other alternative weeklies around the country, including New York’s venerable Village Voice. Most of the newspapers profited off their print editions’ personal — and sex — ads.

Reflecting on their 1970 beginnings, Lacey told New York Magazine in 2007, “It wasn’t easy. I was ready to sell blood to keep the thing going. We’re successful because we’re smart, we outwork everyone. Our papers have broken stories.”

Backpage.com, the digital classified site, was launched in 2004. It soon became a cash windfall. Gross revenue grew from $5.3 million in 2008 to $135 million in 2014, according to the Senate report. The report found that Backpage operates across 943 location sites in 97 countries and in 17 languages.

When the dominant national online classified engine Craigslist bowed to public pressure and stopped posting adult classified ads in 2010, Backpage reaped the benefits. In May 2011, Backpage’s adult section was by far the most popular with more than 1 billion views. No other section, according to the Senate report, had surpassed 16 million views.

As profits soared, Lacey and Larkin maintained ownership of Backpage but in 2012 sold off all of their weekly newspapers, including the New Times.

But critics began accusing Lacey, Larkin and other company leaders of cashing in on the backs of women and children trafficked for sex as early as 2010 when a trafficking victim filed a civil lawsuit in the U.S. District Court of Missouri. The suit was dismissed in 2011.

In that lawsuit, and in subsequent civil actions against Lacey and Larkin around the country, Backpage lawyers argued that Section 230 of the U.S. Communications Decency Act shields them from civil or criminal sanctions. Congress passed the law in 1996 at the dawn of the internet age. And courts have ruled that the statute protects websites from legal liability for the content their users post.

But in the civil lawsuit in Washington state filed on behalf of a trafficking victim, the Washington Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that the suit would be allowed to move forward. The court concluded that Backpage is liable because its editors helped produce the content on the site, rather than just hosting it.

The Senate report details how Backpage moderators would edit out wording indicating a child was underage before publishing such ads on the site.

On April 3, Missouri Rep. Ann Wagner introduced a bill in the House proposing an amendment to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. Wagner’s proposed amendment, referred to as the “No Immunity for Sex Traffickers Online Act,” would add sex trafficking to the list of crimes that are no longer protected by the act. This measure would hold websites accountable for facilitating sex-trafficking offenses involving minors.

Last year, California Attorney General Kamala Harris twice filed criminal charges against Lacey and Larkin and Backpage’s CEO, Carl Ferrer. The first time, a state court judge dismissed the charges, ruling that the Communications Decency Act protected the business from prosecution.

Harris, before taking a seat in the U.S. Senate in January, filed new criminal charges. This time, she included money-laundering charges. And in an appearance before the Senate subcommittee in January, Lacey, Larkin, Ferrer and two other Backpage representatives invoked their rights against self-incrimination and refused to answer questions.

READ MORE: Backpage founders take the 5th

Lacey and Larkin are both also accused of trying to obscure their roles at the company by selling it off to an unknown Dutch corporation, entering into a letter of intent in December 2014. According to the Senate report, the $600 million sale was to Ferrer, with a loan from Larkin and Lacey.

Contributions during 2016 campaign season

Even as their legal troubles escalated, Lacey and Larkin donated $65,000 to Democrats in Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico in late September and October of 2014.

They were also actively contributing during the 2016 campaign season. The Arizona Democratic Party received the most funding from Lacey and Larkin — a total of $40,000 in four separate donations from both men in July and August of 2016. Party Chairwoman Alexis Tameron responded in a statement through a spokesman over email, promising “stricter vetting” of its campaign contributions.

“We’re obviously appalled by any incident of child trafficking and fully support the efforts of law enforcement and the U.S. Senate to investigate their business dealings, including revisiting the notion of immunity from consequences under the Communications Decency Act, of which online advertisers hide behind,” the statement said.

Sinema received a $5,400 donation from Lacey in July 2016, in addition to $5,200 in 2013. The congresswoman’s office ignored more than a dozen requests for comment for this article. Macey Matthews, Sinema’s spokeswoman, eventually responded by email, “Please feel free to use the following response from our office: Congresswoman Sinema did not respond to inquiry.”

On Monday, Sinema spoke to a group at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication in Phoenix, tweeting later that she discussed “the important role journalism plays in a free society.”

When she left the event, a reporter approached her to ask about the Backpage donations. But an aide, Michelle Davidson, put a hand on the reporter’s shoulder to physically block the reporter from approaching Sinema.

U.S. Sen. Tom Udall of New Mexico accepted $10,800 from both Lacey and Larkin in 2016. Through his spokeswoman, Jennifer Talhelm, Udall resolved to donate the money to charity. He said in an emailed statement, “These are very serious and disturbing allegations.”

This February, the Sojourner Center, a shelter for domestic-violence and trafficking victims, filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Phoenix, naming Backpage.com and Lacey and Larkin as defendants. The suit claims resources were “drained” from the center as it saw more trafficking victims, including “at least 15 young women and children trafficked on Backpage.”

READ MORE: Shelter files lawsuit vs. Backpage, founders

Also among the recipients in 2014 was U.S. Rep. Ruben Gallego, who received $2,600 from Lacey. Gallego’s spokesman, Andy Barr, said in an email that the congressman was not aware then of any controversy surrounding Backpage. After the inquiry, Barr said the $2,600 is being donated to UMOM, an Arizona shelter for homeless families.

Mazzio, the filmmaker, said she’s not surprised at how many people seem unaware of the graveness of the allegations. The issue, she said, has not received comprehensive media coverage. “This is the dirty little secret,” she said.

After the 2013 settlement with the county, Lacey and Larkin donated $2 million to ASU’s Cronkite School to fund an endowed chair. The school later returned the funds.

Just before the January Senate hearing, Backpage shuttered the section of its site that hosted the adult ads, asserting that the public pressure for the closure was an “assault on the First Amendment.” In bright red, the word “censored” was emblazoned on the adult-ad landing page.

The statement did not disclose that those ads simply shifted to other sections of the website.

This article was reported and written by students in an investigative-reporting class at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. Their work was supervised by Donald W. Reynolds Visiting Professor Walter V. Robinson, the former editor of the Boston Globe Spotlight Team. Contact the team at [email protected].

READ MORE:

Attorney for Backpage calls raid a stunt

Ex-New Times owners charged in Backpage raid

Read or Share this story: http://azc.cc/2pAXRMA

[ad_2]

Source link