[ad_1]

Facebook has come up with a way to filter the false information out. Veuer’s Aaron Dickens has more.

Buzz60

Dozens of fake news sites are registered in the city, but that doesn’t mean the people running the sites are Scottsdale residents.

Scottsdale is home to many things: Cactus League spring training, hiking trails, the high-profile Barrett-Jackson car auction and, apparently, fake news.

A recent PolitiFact story assembled a database of websites around the world classified as parody, imposter and fake news sites. Of the 201 listed, 64 are registered in Scottsdale — nearly one-third.

While parody sites publish articles that contain false information usually based on current events, imposter sites try hard to look like a legitimate news site and fake news sites publish demonstrably false information.

As fake news came to the forefront of public attention after the U.S. presidential election, platforms such as Facebook have focused on ways to combat the spread of misinformation.

For those running fake news sites, though, publishing conspiracy theories, false medical cure-alls and deliberate misinformation can be a lucrative six-figure business.

Why Scottsdale?

A search into the websites’ registrations of those listed in Scottsdale shows their respective owners all purchased domains from GoDaddy, which is headquartered in Scottsdale.

Domain registrars, like GoDaddy, sell domain names — what you type into your search bar to get to a website — to users who want to create their own websites.

MORE: 5 cool companies you (probably) didn’t know call Scottsdale home

Many of those running the sites do not live in Arizona or have any tie to the state, other than the physical server that hosts their websites.

What makes fake news fake?

Jestin Coler used to publish fake news under a pseudonym in California.

Once Google started cracking down on content that was obviously fake, he switched the paradigm of his most popular site, National Report, from fake news to satire.

Since January, he hasn’t published anything on National Report, but he made a living off what he calls fake news’ “heyday.”

MORE: Phoenix fake-news writer comes clean on Donald Trump

At his site’s peak in 2014, he had about 20 contributing writers. Anyone who treated fake news like a full-time job could handily earn a six-figure salary, he said.

Coler and his colleagues started recruiting and writing for conspiracy theorists and what is now known as the alt-right movement because they were engaged audiences, he said.

“In 2013, we were doing traditional satire and what would now be considered fake news,” he said. “We targeted conspiracy folks — chemtrails, RFID chip folks.”

Despite the reports being fake, people believed them, he said. Over the course of 2014, National Report accumulated about 70 million page views, he said.

But search engines began limiting what sorts of news it would promote, which meant fewer people would see fake news reports, Coler said.

“In January 2015, we saw changes in algorithms that weeded out fake news, so we made the editorial decision to do things that you’d have to try very hard to believe as true,” he said.

However, consumers often read satire and fail to recognize its inherent falsehood, despite the site’s disclaimer that “All news articles contained within National Report are fiction, and presumably fake news,” Coler said.

The site contains satirical articles that could be offensive and are obviously false, bearing headlines such as:

- “Trump to Nominate Chris Christie to Supreme Food Court”

- “Punxsutawney Phil Predicts Four More Years of Snowflakes”

- “Flint Tap Water Rated More Trustworthy than Hillary Clinton”

Since hanging up his satirical and fake news websites, Coler has embarked on national speaking engagements, hoping to illustrate how readers can spot misinformation.

He recently spoke to Harvard’s Nieman Fellows and was described by the fellows’ website as a “recovering fake news publisher.” He said he is writing a book about his experiences in fake news.

Although Coler is now working with media professionals to enhance media literacy, he said fake news is still a money-making business. Even the most absurd content draws clicks — and clicks bring in advertising revenue, he said.

“There is a lot of money to be made,” he said.

Combating fake news

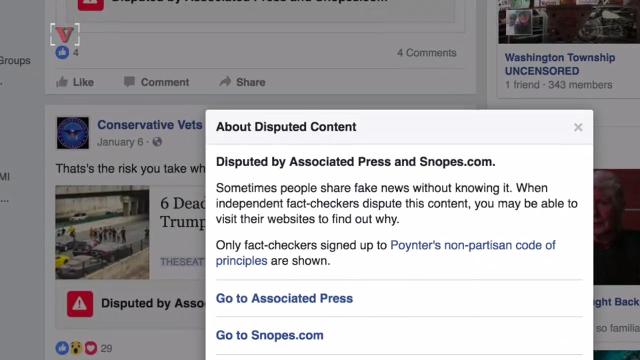

Facebook announced last year it would increase efforts to combat the spread of fake news by its own users.

Joshua Gillin, a staff writer for PolitiFact and the Tampa Bay Times, created the database and has updated it since it was first created in April.

The database started after PolitiFact partnered with Facebook and Poynter, a leader in media ethics, in December to debunk fabrications frequently shared on the social platform.

The partnership resulted in a new tool that would alert Facebook users if an article on their news feed was flagged by fact-checkers.

“If a story’s flagged as being disputed, it will link to Poynter’s code of ethics,” Gillin said. “Any time we come across a site (that peddles fake news) or write about it, we add it to our list.”

Should GoDaddy combat fake news?

While social media platforms such as Facebook are combating fake news, whether or not a service provider such as GoDaddy should is another issue.

“We’re providing the registration of a domain name, we don’t have any access to that content beyond that,” GoDaddy’s Digital Crimes Unit Director Ben Butler said. “We don’t have jurisdiction to try and enforce content rules of anything that’s registered here.”

GoDaddy doesn’t always register a site’s domain, sometimes it also hosts the site’s content, Butler said. In those cases, it may be appropriate for the company to police that site’s content.

In 2008, GoDaddy nixed a site called RateMyCop — a RateMyProfessor-style place where people could critique their interactions with law enforcement. Butler said this resulted in law enforcement officers receiving threats, which allowed GoDaddy to step in and police the site.

Butler said he doesn’t recall if GoDaddy hosted RateMyCop, but the threat to public safety was enough for the company to intervene.

“That was a public safety concern,” he said. “There were legitimate threats being made to the individuals named on the website. Then you’re out of the realm of ‘Don’t believe what you read on the internet.'”

Others also argue it isn’t GoDaddy’s responsibility to determine what the truth is or isn’t.

“Their function is to register domains and provide hosting for what people want to post on their domains,” Arizona State University Professor of Practice Dan Gillmor said. “I certainly would not want to do business with a hosting provider that was deciding what’s true and false — that’s not their job.”

Gillmor teaches digital media literacy at ASU’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication and was involved in the school’s workshop with Facebook to promote news literacy.

He said he supports the ways Facebook has fought the spread of fake news, but doesn’t want to see the social media giant move from flagging content as questionable, to explicitly determining what is right or wrong.

While neither GoDaddy nor Facebook should police content, Facebook is helping people decide for themselves whether something is true or not by flagging it, Gillmor said.

Anything beyond that could quickly become off limits, he said.

“They’re the dominant force in online conversation. For them to decide what’s true or false is a very slippery slope,” Gillmor said. “I think it’s fine if they’re going to make it harder for people to make money on deception. It’s a long way from that to then deciding what’s true and false.”

But Facebook and professors can only do so much.

Media consumers must be able to closely vet their information, Gillmor said.

“I think that a lot of the responsibility for this lies with people who are consumers of information to be skeptical, to use judgment,” he said.

5 ways to spot fake news

A February Associated Press report gave pointers for spotting fake news:

- Look at the URL. If it ends in “.com.co” can be a sign of fake news.

- Look for punctuation. Most legitimate news outlets don’t use exclamation points and all caps.

- Look for other news sites reporting the story.

- Look at fact-checking sites, such as Snopes.com.

- Look at the people quoted in the story and Google them to see if they are real or qualified to be speaking on a given topic.

READ MORE:

Fake news spread by 23% of Americans, study says

Can the fake news trend be de-escalated?

Facebook takes a new crack at halting fake news and clickbait

Phoenix fake-news writer comes clean on Donald Trump

Read or Share this story: http://azc.cc/2rRyCr3

[ad_2]

Source link