[ad_1]

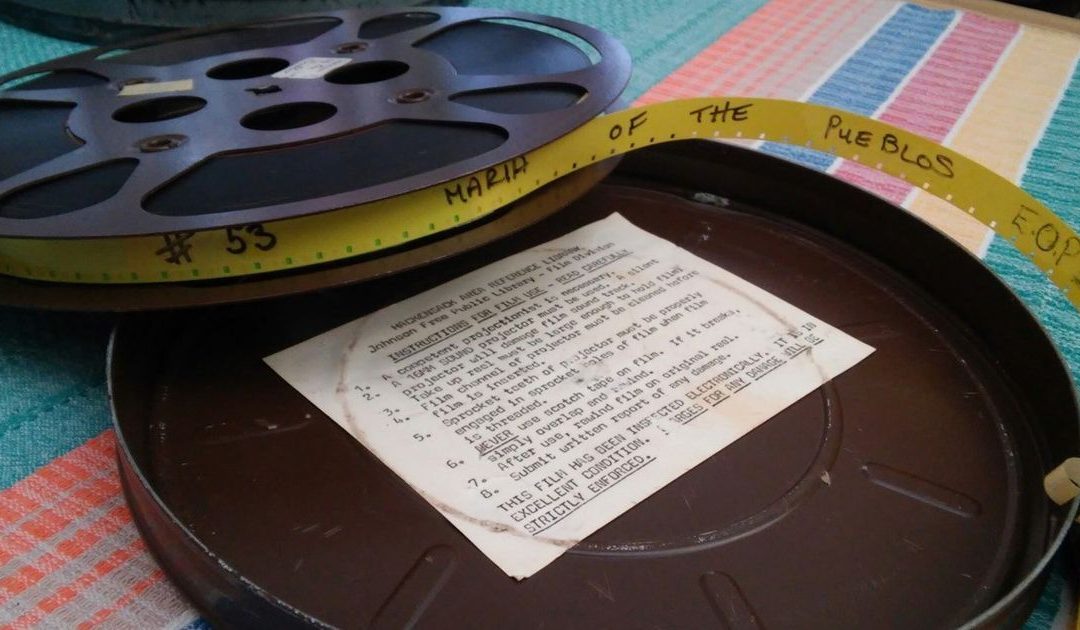

The University of Arizona’s American Indian Film collection features countless Native American faces, the details of their mid-century lifestyles rendered in vibrant Kodachrome.

Their voices, though, are almost never heard.

“There’s quite a disconnect between the visuals, which are absolutely beautiful and rich, and the audio,” said Jennifer Jenkins, an associate professor who specializes in film, literature and archives.

“The narration was meant to present the mainstream cultural attitudes at the time, which could be very condescending. The worst of them are quite racist,” she said.

This summer, a team led by Jenkins will begin “correcting the record” using a nearly $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Members will work with tribal nations to record more authentic narratives in English, Spanish and Native languages, focusing on 60 educational and industrial films specific to Southwestern communities.

“We’re calling it ‘tribesourcing,’ which just means taking the films into the communities represented in them and having those people explain what’s going on on-screen,” Jenkins said. “They’ll explain the cultural practices and ways of life that were glossed over or not really recognized in the original audio. And in many cases, they’ll be able to name the people who appear, which nobody bothered to do previously.”

The university’s film holdings determined the tribal nations included in the project, Jenkins said. Researchers will begin near Tucson and “ripple out,” collaborating with the Navajo, Tohono O’odham, Apache and Pueblo nations, among others.

The effort will take three years.

‘New life’ for films

Rhiannon Sorrell, instruction and digital-services librarian at Diné College, recorded one of the first alternative film narrations as a “tribesourcing demo.”

“Arts and Crafts of the Southwest Indians,” produced in 1940, shows Navajos herding sheep, weaving rugs and visiting trading posts to do business.

The images were “very familiar” to Sorrell, who grew up on the Navajo reservation. But the commentary — “delivered in this booming, very authoritative ‘voice of God'” — sidestepped explanations of the activities presented.

“I wanted to record a response that was much more educational or informative, versus the touristy kind of spiel often provided in these films,” she said. “But I was really intimidated when I first started, because I wasn’t sure to what extent I was allowed to provide personal commentary and to what extent I was supposed to provide educational insight.”

Ultimately, Sorrell recorded a mix of her own childhood memories and information culled through archival research. She will help other Navajos do the same as a liaison for the film project, ensuring the process respects Navajo rules and customs, she said.

Some narrators will record alone, like Sorrell, while others might work in pairs or teams. They can prepare scripts or simply speak about what they’re seeing on the screen in real time, Jenkins said.

“We’ve identified quite a big network of people to serve as narration coordinators within the tribes, through friends, former students and graduate students,” Jenkins said. “I think it’s really important to give this footage new life in a culturally sensitive way.”

‘Speaking for themselves’

That “new life” will include educational modules for grade-school and university students, according to Amy Fatzinger, assistant professor of American Indian Studies and the project’s outreach facilitator.

Fatzinger plans to develop lessons on the topics addressed by the new narrators, with the films and related materials housed online.

“In the course I teach at the university, ‘Many Nations of Native America,’ I always begin with an exercise where students get an index card and draw the images they associate with American Indians,” she said. “I’ve done that same test with fourth-graders and gotten almost identical results.

“It’s really remarkable how consistent it is, so I’m thinking it wouldn’t be terribly difficult to develop modules with those starting points in mind,” she said.

The modules will retain the films’ original narration as an audio option, she said, because those tracks are “also worth examining and studying.” Though the “outsider point of view is often very inaccurate,” she said, it allows the listener to learn about prevailing attitudes at the time.

The team also hopes to host film screenings and conversations on the reservations.

“We want anyone who wants to see this content be able to come and participate,” Fatzinger said. “This whole project is a really unique opportunity to allow the people in these communities to speak for themselves.”

READ MORE:

Gila River member becomes 1st Native American to have a vote on Arizona water board

Arizona four corners: Read stories from across the state

The Navajo Nation accepted more than $1 billion for houses. So, where did it go?

Navajo Nation officials want President Donald Trump to subsidize Kayenta Mine, power plant

Read or Share this story: http://azc.cc/2paDHZx

[ad_2]

Source link