[ad_1]

A look back on the talented player’s NFL start and the series of events that ultimately resulted in his death.

USA TODAY Sports

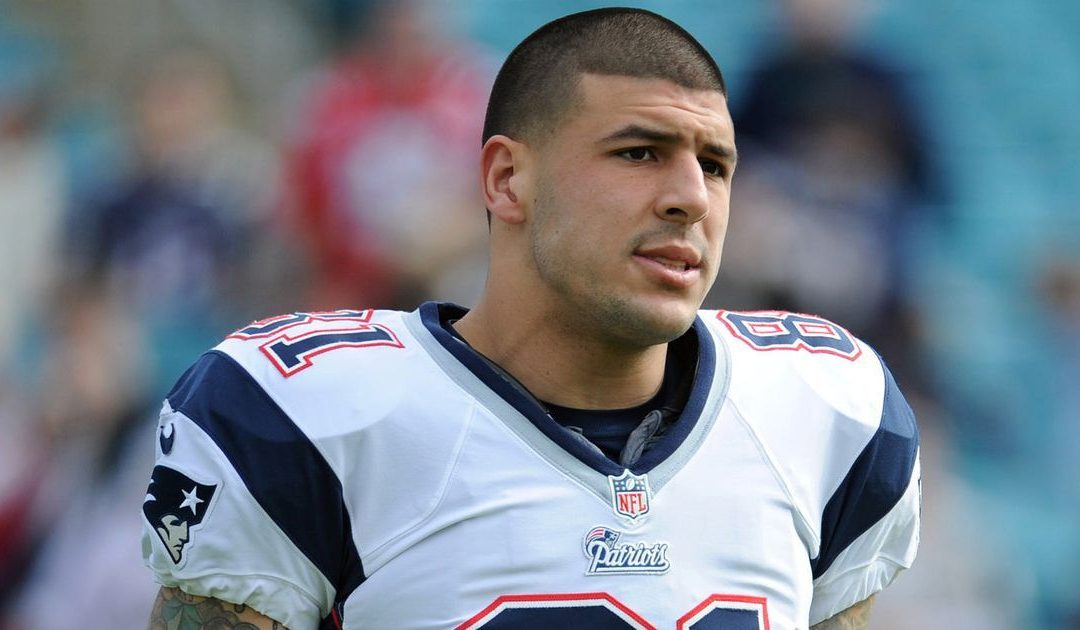

Aaron Hernandez grew up in Bristol, Conn., home of ESPN, and he had the sort of athletic gifts that would lead one day to SportsCenter highlights and multi-million-dollar contracts to play for the darlings of his region, the New England Patriots.

But the boy from Bristol also harbored demons of the sort that would one day lead him to drugs, accusations of cold-blooded murder and, finally, his own death. Authorities said he hanged himself with a bed sheet early Wednesday in the prison cell where he was serving a life sentence without possibility of parole. He was 27 and had lived an operatic hybrid of American dream and ghastly nightmare. His death came the same day his former team visited the White House to celebrate their Super Bowl victory two months ago.

Hernandez caught a touchdown pass in the Super Bowl in early 2012 – and the next year found himself accused of killing a semipro football player, Odin Lloyd, who was dating the sister of Hernandez’s fiancée. Motive remains unclear, though it may have been that Lloyd had some knowledge of Hernandez’s link to a double homicide in the summer of 2012.

Last week, Hernandez was acquitted of the most serious charges in that case, which would have only added to his life sentence because Massachusetts does not have the death penalty. Though, in the end, Hernandez apparently imposed his own.

MORE COVERAGE:

Armchair psychologists will long speculate what took Hernandez from a top target for Tim Tebow in college football to a top target for Tom Brady in the NFL and from there to a dark side of malevolent violence and unfathomable anger. Answers are ultimately unknowable but clues abound, beginning with the unexpected death of his father in 2006 when Hernandez was 16.

Dennis Hernandez was a high school custodian who died of complications arising from routine hernia surgery. The aftermath “was a mess with a lot of family issues, fighting and disagreements,” Hernandez told USA TODAY Sports in 2009, when he was playing at Florida.

“I didn’t know what to do for him,” his mother Terri said in the same story. “He would rebel. It was very, very hard, and he was very, very angry. He wasn’t the same kid, the way he spoke to me. The shock of losing his dad, there was so much anger.”

Trouble ‘finds this guy’

Hernandez was an honor student at Bristol Central High School, though Doug Pina, his high school coach, told the Hartford Courant in 2010 that he’d personally “always had concerns” about him.

Hernandez had originally planned to play college football for Connecticut, where his father and older brother played, but changed his mind and chose Florida. Before his first college game, Hernandez, then 17, punched a restaurant manager in the side of the head, busting his eardrum in a dispute over the bill. The case apparently settled out of court.

Hernandez also was among several Gators players interviewed by police after a shooting at a nightclub that left two men wounded. No one was ever charged.

Hernandez won a national championship and the John Mackey Award for the nation’s best tight end during his time at Florida. He declared for the 2010 NFL draft where the Patriots took him in the fourth round, lower than his talent suggested he’d go, apparently because of multiple failed drug tests and unsavory friends. CBSSports.com quoted an unnamed NFL scout: “We stayed away because we hated the people he hung out with and how trouble always finds this guy.”

MORE COVERAGE:

Published reports at the time said Hernandez had told teams at the NFL scouting combine that he’d begun using marijuana to cope with the death of his father.

“Who do I talk to?” Hernandez said of the uncertainty after his father’s death in that 2009 USA TODAY Sports story. “Who do I hang with?”

He often hung with a bad crowd in years to come, including Ernest Wallace and Carlos Ortiz. Rolling Stone styled them as “two stumble-bum crooks with long sheets of priors.” Wallace and Ortiz were with Hernandez when Lloyd was killed near Hernandez’s Massachusetts home in 2013.

Family relationships were often complicated. Hernandez’s cousin Tanya married Jeffrey Cummings in 2005; they had a son together and got divorced. Then, in 2009, Cummings married Hernandez’s mother on a trip to Las Vegas. A year later, about a month before Hernandez reported to his first Patriots’ training camp, Cummings slashed Hernandez’s mother with a knife and she had lacerations to her face, shoulder and wrist. Cummings would wind up in jail and they would divorce.

Hernandez married Shayanna Jenkins in 2012 in the same month their daughter was born. That came only months after two Cape Verdean immigrants were gunned down in their car drive-by style after one of them bumped into Hernandez at a nightclub and spilled his drink.

Alexander Bradley would say at trial that it was Hernandez who shot Daniel de Abreu and Safiro Furtado – and Hernandez’s lawyers would say it was Bradley who shot them. Bradley, not incidentally, had filed a civil suit in 2013 alleging that Hernandez shot him point-blank in the face months earlier, costing him his right eye. They were best friends before they were mortal enemies.

Tattoos tell story

Last week, Hernandez wept after he was acquitted. It seemed out of character for a man who so often seemed devoid of any emotion. Reports at the time of his father’s funeral said that Hernandez didn’t cry, even as his brother and so many others did.

“There was such hunger in that kid for a father’s hand, and such greatness itching to get out,” Rolling Stone’s story said after Hernandez’s arrest in 2013, “that coach after coach had covered for him whenever the bad Aaron showed — the violent, furious kid who was dangerous to all, most particularly, it seems, to his friends.”

Kelly Whiteside wrote in her 2009 story in USA TODAY Sports that a guided tour of the tattoos on Hernandez’s body reads like his autobiography.

Starting from his right shoulder, she wrote, “there was a tattoo representing God’s hands, a nod to his big brother and to his father and the day he died. There’s the sun representing all the good days he had with his dad. Beneath those rays are clouds and rain.”

Hernandez then pointed to the angels near his wrist. “It all ends in heaven,” he said.

He’d add more tattoos in the years ahead. One was of a smoking semi-automatic pistol. Another was of a six-shot revolver. That one accompanies two words, written in reverse: “God Forgives.”

PHOTOS: Aaron Hernandez’s life

[ad_2]

Source link