[ad_1]

Tony Dow is at peace with Wally Cleaver.

Mostly. Finally.

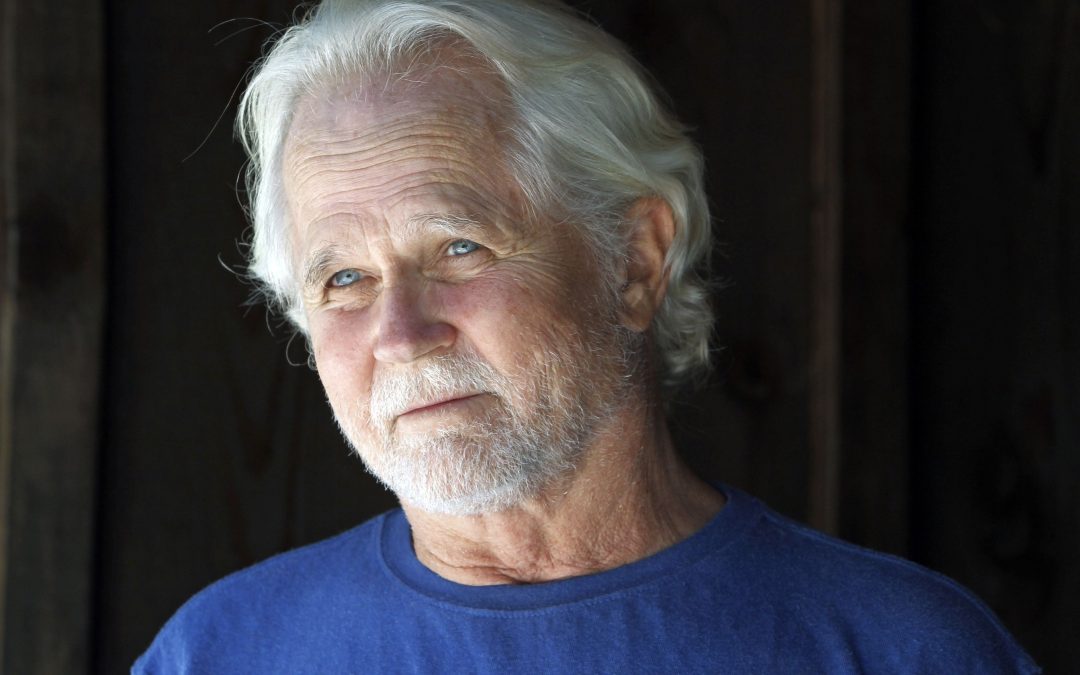

Dow, 72, retains a boyish innocence and charm. An afternoon at his longtime home in the Santa Monica Mountains near Malibu, California, moves at a pace much like that of the Cleavers’ days six decades before.

His first car, a 1962 Chevy Corvair Spyder, sits parked under a two-car open garage.

With “Leave It to Beaver” celebrating its 60th anniversary Wednesday, it would be a tragedy of one of America’s enduring television comedies if Dow could not at least co-exist with his character and the show.

“Leave It to Beaver” has been available over the air to Baby Boomers and subsequent generations without interruption since its original run from 1957 to 1963.

The direct monetary residuals dried up long ago, after the first-time showing and six repeats of the 234 black-and-white episodes. But the residual love of the show’s fans never dies.

“It’s nice to be remembered any way you can, so I have accomplished that,” Dow says. “I’m much more appreciative of the show. I was not unappreciative, but I was always a little rebellious.

“And I was a little angry that when I’d go after parts, a lot of the times I wouldn’t get them because I was too identified with the Wally character.”

But any latent rebelliousness comes with the recognition that those involved with the series produced something special in the fictional town of Mayfield.

“I think it’s amazing they did that show 60 years ago and it’s still relevant,” he says.

It’s not just typecasting as the elder Cleaver son that created ambiguity for Dow, who grew from eighth to 12th grade on the show and served as a buffer between his earnest parents and his younger brother. (He was “Beaver,” as we learned in the series finale, because 5-year-old Wally could not say Theodore.)

Since 1963, when the show ended its six-season run, Dow has lived a life in multiple acts, including as a director and as a sculptor.But lessons from the show and his teenage years stuck with him, through struggles with depression and two different cancer scares.

“I’ve learned to take things less seriously,” Dow says. “I always thought if you’re going to do something, do it better than anybody else can do it, even if it’s sweeping up the broom closet.

“I learned it’s OK for me to not be assertive, especially now. I’m perfectly happy making sculpture and living where we live.”

Prelude: Johnny Wildlife

Dow was born into show business, to some extent.

His mother, Muriel, was a Mack Sennett bathing beauty and an acting double for 1920s star Clara Bow, although Dow says she only was interested because movie studios were located near Hollywood High School and she was looking for fun and adventure.

“When she married my dad (contractor John Dow), he wasn’t interested in the business at all, so she moved away from it. Like any mother, she wanted the best for her kid.”

The best didn’t include acting at an early age like Jerry Mathers (Beaver Cleaver), who started at 2. Dow’s early prowess was as an athlete.

He was a diving champion up to the Junior Olympic level before and during the “Leave It to Beaver” years, winning a boys 14-under 1-meter title at a meet in Phoenix in 1958 at the famed Dick Smith Swim School. Future Olympians Patsy Willard and Jeanne Collier were in the senior women’s field.

Acting came into the picture, not because of his mother but when an older lifeguard friend from the Hollywood Athletic Club auditioned for the lead role of a show called “Johnny Wildlife,” bringing Dow along because there was some resemblance between them.

“Johnny Wildlife” would have changed everything for young Dow.

By April 1957, when he turned 12, Dow had been cast as the son of a wildlife photographer and shot the color pilot show in a still predominantly black-and-white TV era. The adult role did not go to Dow’s friend, rather to acting veteran Paul Langton, best known for a later role on “Peyton Place.”

“It was a great concept,” Dow says, but ahead of its time in raising environmental concerns. The project also was tripped up by the technology of the day.

“The pilots we did dealt with Japan going over the quotas of (hunted) whales and a company dumping toxic waste into the ocean,” he says.

“But they were writing to a lot of stock footage that didn’t match the footage they shot. They couldn’t balance the colors. It would have worked in the ’70s or ’80s or even now.”

According to Billboard, among the 182 other new shows being pitched that spring to advertisers was a pilot in production then called “Wally and The Beaver.”

“Johnny Wildlife” failed to make the cut for any of three national networks, but the renamed “Leave It to Beaver” did on CBS.

Dow, though, was in demand and had a choice of offers immediately after “Johnny Wildlife”: as a Mouseketeer on the “Mickey Mouse Club,” as Boy to Gordon Scott’s Tarzan — and as Wally Cleaver.

Paul Sullivan played Wally in the pilot — televised in April 1957 on the anthology series “Studio 57” under the title “It’s a Small World” — then quickly outgrew the role on his way to 6-foot-5.

So Dow found himself at a Hody’s restaurant listening to his mother’s opinion that “Leave It to Beaver” probably had more potential than his preference, as an accomplished diver, for playing Boy.

“I said OK, took a bite of my cheeseburger, and that was it,” Dow says. “It wasn’t a hard sell.”

Tony Dow was 12 when “Leave It To Beaver” went on the air Oct. 4, 1957. Now 72, Dow, who played Wally Cleaver, along with Jerry Mathers (Beaver) and Ken Osmond (Eddie Haskell) are celebrating the 60th anniversary of the show. Jeff Metcalfe/azcentral

Wochit

Act I: Wally Cleaver

“Leave It to Beaver” never cracked the Nielsen top-30 ratings in an age when TV Westerns were king. After its first season, the show moved from CBS to ABC, at least in part because of a better deal arranged by sponsor Ralston Purina. It stayed there for the remaining five seasons.

Ratings aside, something special was happening in fictional Mayfield that has stood the test of time.

Creators Joe Connelly and Bob Mosher, who wrote many of the early episodes, understood the humor in their own lives — they had a combined eight children — and how to translate that on television by telling stories from a youth’s point of view rather than an adult’s, as was done on “Father Knows Best” and other contemporary comedies.

“Outside of ‘The Wonder Years’ (1988-93), I don’t think there’s been another show that’s done that,” Dow says. “It’s a really valid way to tell a story because you can tell the craziness of the adult world through the kids’ eyes, and it has some meaning for both the kid and for the adult.”

Dow is a longtime friend with Billy Gray, who has mixed feelings about playing teenage son Bud Anderson on “Father Knows Best.”

In a recent interview on Baby Boomers Talk Radio, Gray took issue with the idyllic family portrayed on his show from 1954-60: “It purported to be an example to live by,” Gray said. “That’s a very insidious thing. Your example is perfect, my family must be (expletive) because it isn’t like real life on TV.”

Some similarly criticize “Leave It to Beaver,” but not Dow. “I don’t think of it that way,” he says. “I think it’s a safe place to go, a thing to aspire to.”

A common college sociology assignment now is to compare the TV family as portrayed on “Leave It to Beaver” with, say, “Modern Family” or before that, “Married With Children.” Dow believes there are things to learn from such studies but only goes so far with his analysis.

Some of the most-criticized elements of “Leave It to Beaver” were cosmetic rather than symbolic, he says. Barbara Billingsley (June Cleaver), for example, often wore pearls to cover an indentation in her neck, he says.

“People are always saying that’s not like real life,” Dow says. “My mother would never vacuum in heels or Dad doesn’t wear a suit and tie to dinner. Those things were superficial and there was a reason for most of them. The stories themselves were all from real life, and they all had a point.”

The point being that no matter what — Beaver climbing into a bowl of soup on a billboard, Wally insisting on having a jelly-roll hairstyle or even what has been described as Eddie Haskell’s soft-core delinquency — the nuclear family would pull together and prevail.

“Leave It to Beaver” and the Soviet satellite Sputnik launched on the same day, a coincidence that has come to symbolize an innocent beginning to an era transformed in the 1960s by the Cold War space race, Vietnam and all that Woodstock represented.

“By suggesting the emotional turbulence underneath the idyllic surface, Beaver paralleled the actual experience so many of the show’s fans had growing up in real-life suburban families,” an essay posited on Interestingideas.com.

Dow sees Wally as an interpreter of sorts, explaining to Beaver what their father, Ward, means with his lesson stories or bringing the wisdom of his extra five years — there is some age and grade confusion over the course of the series — to bear in explaining life to his brother. Such as this exchange from Season 3 when Ward’s reading recommendation leads to Beaver getting into fights while trying to right wrongs.

During the run of the series, Dow says, he, Mathers and other minors in the cast were asked not to view the finished product. “They definitely didn’t want us to think we were funny or that we were big shots,” sounding for all the world like Wally. “I’ve never been interested in watching myself (on screen). Even now, unless I see a show, I don’t remember the scenes. But I’m enjoying them more now because there’s stuff I didn’t understand when I was a kid.”

Dow sees an episode such as “Happy Weekend,” which aired on Christmas Day 1958, in an entirely different way than when he was a teen. Now he is the adult, understanding Ward’s wistful desire to take his sons to Shadow Lake to fish and explore like he did as a child. Beaver and Wally, though, prefer to stay home in order to watch the movie “Jungle Fever” with their friends.

“I thought they’d have fun doing the kind of things I did when I was their age. But I guess you can’t wrap your childhood up in a package and give it to your kids,” Ward says to June.

It’s a scene that symbolizes “Leave It to Beaver” for Dow. “That’s a simple theme — you can’t go back — which is very true,” Dow says. “That’s the kind of universal message they were creating.”

The “Leave It to Beaver” six-season run ended in June 1963, when Dow was 18. It had reached a natural ending point, with Wally reaching college age and Beaver about to enter high school. The final episode, “Family Scrapbook,” is a clips show directed by Hugh Beaumont (who played Ward Cleaver), considered to be one of the earliest prime-time series finales.

Dow was ready to move on, but to what?

Act II: Behind the camera

He was ready for serious roles after “Leave It to Beaver,” but not many were offered other than the first. But he always had a vision of directing, stoked by director Norman Tokar, as his Plan B.

In fall 1963, Dow landed a role as a teen unwed father for a two-part episode that began on “Dr. Kildare” and continued on “The Eleventh Hour.”

Even now he believes “Four Feet in the Morning” was the best acting of his life, and director Jack Smight had a profound impact on his future. The episode won an American Cinema Editors award but, Dow says, because of the first-time crossover between series, it was not submitted for Emmy consideration.

“I’m sure it would have gotten some awards,” he says. “I doubt if I would have, but at least it would have been a huge boost to my career.”

Being mostly typecast as Wally Cleaver “bothered me quite a bit because I was trying to be serious as an actor, and I was continually getting these apple-pie roles.”

In the 1977 sketch comedy film “The Kentucky Fried Movie,” Dow took a poke at Wally, wearing a letter sweater as a juror while sitting next to Beaver, played by Jerry Zucker, in a courtroom scene set in 1957 and like “Leave It to Beaver” shot in black and white.

He was back playing grown-up Wally Cleaver in a 1983 reunion movie that led to the “The New Leave It to Beaver,” which included Mathers, Billingsley and Ken Osmond (Eddie Haskell) and ran until 1989, adding 105 more episodes to the Beaver legacy.

There also was a “Love Boat” appearance as Wally in 1987 and a cameo in the movie “Dickie Roberts: Former Child Star” in 2003. But by then, Dow was well into his directing career, which began on “The New Leave It to Beaver.”

“Jack Smight probably influenced me more than anybody,” Dow says. He went to watch dailies (unedited footage) with Smight during the filming of “Four Feet in the Morning” and listen to the Emmy-winning director discuss editing.

Dow trained at the Film Industry Workshop and Sherwood Oaks Experimental College “with the eye that I wanted to direct” but blames his lack of assertiveness on not breaking into that part of the business sooner.

“When you’re not assertive, people don’t listen. That’s been part of my whole life. I usually have really good ideas, but I just don’t present things the right way,” he says.

Such was the case in 1996 when his friend Brian Levant, executive producer of “The New Leave It To Beaver”and co-writer of the movie script, had to pass on directing a “Leave It to Beaver” movie because he was committed to “Jingle All the Way.”

Levant recommended Dow. Dow says Levant told him “you’ve got to make them (producers) think you’re going to make this movie much bigger” than the TV original.

Dow had something different in mind: a 1950s retro film. But he didn’t get the opportunity.

Instead, with Andy Cadiff of the television sitcom “Home Improvement” at the helm, the Beaver movie largely bombed. The New York Times review complained that it was neither nostalgic enough (like Dow imagined) nor fully satirical.

Dow considers a 2000 episode of a short-lived TV show “Cover Me: Based on the True Life of an FBI Family” to be among his best directorial work. He also thought he was successful at “making Craig T. (Nelson) more appealing to women” in the 12 “Coach” episodes he directed.

During this period, Dow went public about being treated for depression to encourage others to do the same. He also survived prostate cancer and gall-bladder cancer.

Eventually, though, directing, like acting, became a chore for him, “because you have to psychologically deal with so many different kinds of temperaments and personalities,” he says.

But there was yet another act to come in his life, over which creatively he has final control.

Act III: Abstract artist

Dow never confined himself to expressing himself athletically or as an actor/director. His creative mind always went beyond show business in ways he did not fully explore until after the fateful day a clueless young director asked during an audition, “Have you ever done comedy before?”

That became not only one of his go-to stories but a tipping point for getting serious about sculpting in 2000.

Dow remembers his parents buying him an acetylene torch when he was 18. The why is a little vague all these years later, but he began brazing metal together to create sculptures for local arts shows. He painted, too, and made a colored pencil drawing of a Spanish galleon for his TV mom, Billingsley.

“I was always kind of fooling around with (arts) stuff,” says Dow, who also has worked as a contractor and has done most of the work since 1986 on his Topanga Canyon home.

He once had a dream of converting a wooden post office near the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California, into a home/arts gallery but realized it would be financially impossible.

At Topanga, though, Dow had room to build a studio and the natural resources from fallen trees to create burlwood sculptures, some of which are then bronzed.

“I just start out, then I start seeing something and say, this is what I want to do, then I start refining it,” Dow says. “It may come out that way or it may come out a different way. But the creative process is really a spooky thing. I’m completely happy if the wing falls off to do something else. I’ll use it as a positive.”

This summer, the Dows — Tony and his wife of 37 years, Lauren — were adapting to life with a new dog, Poppy, a fittingly black-and-white Bergamasco shepherd with an it-wasn’t-me face that begs to be on television. Soon, Poppy the large puppy will be in trouble for drinking from a visitor’s glass.

The Corvair Spyder also is new to the house, in a way. Alan Dadisman, who once built props for Universal, bought the car from Dow years ago. When Dadisman died last year, he requested that the midnight blue Corvair be returned to Dow, and there it sits in Topanga, leaking oil but still treasured.

There is more evidence of Dow the sculptor at his home than Dow the actor. A large framed photo of the “Leave It to Beaver” family leans against the wall in a spacious den with full-window views of the canyon on two sides. Otherwise, a visitor would not know the erstwhile Wally Cleaver is a resident.

Dow originally wanted to keep his artistic and show-biz life separate, signing autographs at gallery openings T Dow for a time to draw a line that he soon realized was impractical to enforce. His pieces now are being sold at Bilotta Gallery — Home of Celebrity Artists — in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, along with those of actors Eve Plumb, Burt Young, Rosie O’Donnell and Billy Bob Thornton, among others.

Once his abstract sculptures, many of which sell for $5,000 or more, were being shown at a gallery in Scottsdale, he says.

“I was really excited about it, then I had a friend stop in to tell me where my stuff was. The bigger piece was on the ground, which was fine. He asked, ‘Who is the artist who did these?’ and the guy said, ‘Some old actor guy.’ How the hell are you going to sell anything like that?”

“The Diver,” originally commissioned for the International Swimming Hall of Fame, is one of Dow’s bronze castings. He did a burlwood piece called “Athlete” representing his love of volleyball. On a tour of his home, he points out “Complicated Man” (a burl assemblage) and other pieces inspired by his sculpting hero Henry Moore.

Then there’s “Unarmed Warrior,” a bronze of a woman holding a shield. It was selected in 2008 for the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts exhibition at the Carrousel du Louvre, an exhibition hall within the Louvre Museum in Paris. The exhibition dates to 1862 and was revived in 1890 with Auguste Rodin, another influence on Dow, as president of the sculpting section.

“It was a juried show, and there were only two sculptors from America and 20 countries represented,” Dow says. “It’s one thing that celebrity had nothing to do with.”

EPILOGUE: THE LEGACY

Brian Levant and Dow go back almost 40 years, predating their work together on “The New Leave It to Beaver.” He understands the original show’s place in television history as well as anyone and can catalog the accomplishments of creators Bob Mosher and Joe Connelly, from “Amos and Andy” on radio and TV in the 1940s and 1950s through “The Munsters” of the 1960s.

“They were unsung heroes in television and among the very first independent writer-producerswho owned their shows,” Levant says. “Rod Serling and Paddy Chayefsky turned television into a writers’ medium, and Bob and Joe were a huge part of it.”

It might seem a stretch to put “Leave It to Beaver” in any category with “The Twilight Zone” (Serling) or “The Philco Televison Playhouse” (Chayefsky), yet the good-hearted comedy has outlived almost all of its contemporaries. Levant puts only “I Love Lucy” and “The Honeymooners” in the same longevity category.

Levant currently is teaching a class called Sitcom Boot Camp at his alma mater, the University of New Mexico. He included a clip in a lecture from an episode in Season 4 called “The Dramatic Club,” where Beaver agonizes over having to kiss a girl in a school play.

“That’s as fresh and universal as 1960,” Levant says. “It’s the universality of growing up. Discovering your mother bought a girls sweater and you have to wear it to school (“Beaver’s Sweater,” Season 2) or breaking a window (“The Broken Window,” Season 1) happen generation after generation. People can malign it, but nine out of 10 stories came from real life.

“If you say it’s fluff, you’re not paying attention as the show got older and grew up and turned more to Wally and his friends and their difficulty transitioning to adulthood. I’m still overwhelmed with how good those episodes are and how simple.”

It’s not hard to find “Leave It to Beaver”influence, coincidental or direct, across the entertainment landscape or in pop-culture references.

“American Graffiti,” made in 1973 by George Lucas, includes a scene straight out of “Wally’s Practical Joke” (Season 6) 10 years before. Richie Cunningham is stuck dating a much taller girl in “Happy Days” in 1974 just like Wally in 1961 (“Wally’s Big Date,” Season 5). Ralphie must wear a bunny suit in “A Christmas Story” (1983) as did Beaver in 1962 (“Beaver, the Bunny,” Season 5). The premise of “The Sandlot” (1993) is virtually identical to “Ward’s Baseball” (Season 3) in 1960.

In 2004, communications professor/author Stephen Winzenburg rated “Leave It to Beaver” 14th in his book “TV’s Greatest Sitcoms.” Time magazine included the program among its ranking of the 100 best TV shows of all time in 2007.

The premier episode, “Beaver Gets Spelled,” earned a 1958 Emmy nomination, as did the series for best new program.

What if?

Dow’s piece of the legacy is undeniable. Even as an acting newbie in Episode 1 — “I didn’t know what the hell I was doing” — he delivers a laugh-out-loud scene while pecking a typewriter reply to Beaver’s teacher for what the boys believe to be a note about Beaver’s bad behavior.

“To say it’s not without influence is not true at all,” Levant says. “It’s a show that just keeps living when everything else has fallen by the wayside, shows that were higher-rated, with big stars and a lot more money.”

Levant believes actors can’t hide who they really are on TV and that on “Leave It to Beaver” the main characters were “as much like the real people as you could possibly imagine. Tony was and is a guy you could trust with your secrets and will never turn on you no matter what you do. He is dripping with decency and honesty. All the qualities I admired on TV, he brings to our relationship.”

Ward and June couldn’t ask for anything more from a grown-up Wally.

Dow is close with Mathers and not necessarily envious of his star billing from “Leave It to Beaver.” But Dow does believe he deserves his share of credit for the show’s iconic status.

What if the show’s original title “Wally and The Beaver” had not been discarded because it could be confused for a nature program or “about a kid and his pet beaver,” Dow wonders.

He doesn’t consider himself “second banana” to Mathers’ Beaver but believes many do.

“I would have been on more of an equal level with Jerry. I get the feeling sometimes people are always wondering how did I like working with Jerry. I loved working with Jerry, but we were both there the same amount of time and put the same energy into the show. For him to be considered star of the show, it probably would have been different if it was ‘Wally and The Beaver.'”

‘Leave It to BEaver’

First telecast: Oct. 4, 1957.

Last telecast: June 20, 1963.

Total episodes: 234 (6 seasons).

Primary cast: x-Barbara Billingsley (June Cleaver), Jerry Mathers (Beaver Cleaver), x- Hugh Beaumont (Ward Cleaver), Tony Dow (Wally Cleaver), Ken Osmond (Eddie Haskell). (x-deceased).

Mathers, 69, served in the U.S. Air Force Reserve after the show and then went to college at the University of California. He returned to acting in the late 1970s, including his stint on “The New Leave It to Beaver.” Today, he frequently makes personal appearances, including in support of how to manage Type 2 diabetes, which he was diagnosed with in 1996. His autobiography, “And Jerry Mathers as the Beaver,” was published in 1998.

Osmond, 74, did some acting after the show before joining the Los Angeles Police Department in 1970. He survived a shooting incident in 1980 in part because he was wearing a bulletproof vest, then was placed on disability. Osmond returned to television for “The New Leave It to Beaver.” He is co-author of “Eddie: The Life and Times of America’s Pre-eminent Bad Boy,” published in 2014.

Supporting cast: Rusty Stevens (Larry Mondello), x-Stanley Fafara (Whitey Whitney), Stephen Talbot (Gilbert Bates), x-Frank Bank (Lumpy Rutherford), Rich Correll (Richard Rickover), Jeri Weil (Judy Hensler), x-Sue Randall (Miss Landers), x-Richard Deacon (Fred Rutherford). (x-deceased).

Broadcast history: Since its original run, “Leave It to Beaver” has aired continually in syndication and more recently on TV Land, Retro TV, Antenna TV and currently Me-TV.

Sequel series: A reunion telemovie “Still The Beaver” aired in 1983, followed by a series by that name on the Disney Channel from 1985-86. Then “The New Leave It to Beaver” ran on TBS from 1986-89 (105 episodes).

‘Leave It to Beaver’ first TV run

1957-58 (CBS): 7:30 p.m. Friday vs. “Saber of London” (NBC), “Adventures of Rin Tin Tin” (ABC).

1958-59 (ABC): 7:30 p.m. Thursday vs. “I Love Lucy” reruns (CBS), “Jefferson Drum” (NBC).

1959-60 (ABC): 8:30 p.m. Saturday vs. “Wanted: Dead or Alive” (CBS, No. 9 highest rated for season), “Man & The Challenge” (NBC).

1960-61 (ABC): 8:30 p.m. Saturday vs. “Checkmate” (CBS, No. 21 highest rated for season), “Tall Man” (NBC).

1961-62 (ABC): 8:30 p.m. Saturday vs. “The Defenders” (CBS), “Tall Man” (NBC).

1962-63 (ABC): 8:30 p.m. Thursday vs. “Perry Mason” (CBS, No. 23 highest rated for season), “Dr. Kildare” (NBC, No. 11).

[ad_2]

Source link