[ad_1]

5 things to know before seeing the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera exhibit at the Heard Museum.

Wochit/TreNesha Striggles

The truck and its guards snaked through downtown Phoenix after midnight, carrying the precious cargo to its destination on Central Avenue. Outside the truck, the streets hummed. The Final Four was in town, and everywhere was a party. Bars were filled to capacity, pulsing music pouring onto sidewalks. Keith Urban played a concert in the park, backed by a Ferris wheel and twin spotlights that pierced the sky.

There was even a party at the Heard Museum, so the truck went around back.

Behind the museum, the truck stopped, the engine still running. It was 1:30 a.m. Couriers from the Mexican government checked a serial number that hung from the trailer on a metal tag. Satisfied, the driver cut the engine, and the truck’s hydraulic door inched up.

Inside were wooden crates, 33 of them, built like pieces of fine furniture and lined with padding to protect what lay inside: Priceless paintings by Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, brought to the Heard Museum for the only North American stop on a worldwide tour.

5-month Frida Kahlo exhibit in Phoenix

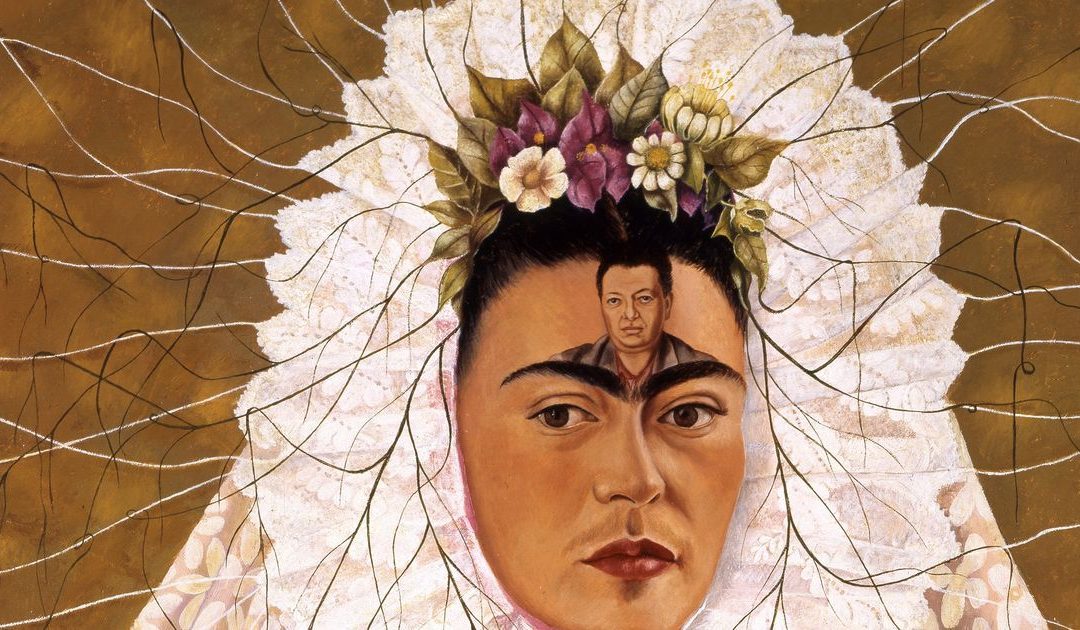

The five-month exhibit is anchored by world-famous Kahlo pieces such as “Diego on My Mind,” in which her husband’s face is superimposed on her forehead, the intense stare of her “Self-Portrait with Monkeys,” and Rivera’s renowned canvases of calla lilies. It’s the kind of attention-drawing collection that Heard Museum staff has long chased, pushed by an ambition to turn Phoenix into one of America’s top cities for fine art.

David M. Roche, the Heard’s director and CEO, watched as couriers carried the crates into the museum. Roche examined the layers of travel stickers that covered the wood. Each piece had traveled the world, basking in the sort of notoriety that didn’t come to Frida Kahlo until after her death. In life she was Diego Rivera’s wife, a young woman with failing health and a famous husband. Now her name was listed first, and “Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera” had become one of the most coveted collections in the art world.

“Frida is always high-demand,” said Robert Littman, director of the Vergel Foundation, which controls the collection of Jacques and Natasha Gelman. The Gelmans were fervent art collectors, and after their death left 95 pieces by Mexican artists to Littman. Included in that set were some of Kahlo and Rivera’s most well-known works, which became the highlights of this three-stop tour.

From Australia to Italy to Arizona

The tour spent its first five months in Sydney, where the demand for tickets forced the Art Gallery of New South Wales to extend the exhibit by two weeks. Next came four months in Bologna, Italy, where 200,000 people waited in lines that stretched to four hours long. When the Bologna exhibit closed and couriers packed the paintings into their crates, they heard would-be visitors knocking on the glass, begging for one more look.

Another American museum had booked the tour’s final stop, but canceled. The paintings were headed across the Atlantic anyway — as Mexico’s most treasured works of art, they’re required to return to the country every two years for inspection — so last February Littman called a friend in Phoenix.

“Would you be interested?” he asked Roche.

“We were stunned,” Roche would recall later.

Roche was just a few months into his tenure at the Heard, the prominent Phoenix museum that spotlights Native American art and culture. It felt too soon to organize an event that would require so much of the museum’s budget, but he had brought with him a new mission statement: “To be preeminent,” Roche said. “To be world-class.” He accepted, and so began the year-long process of shipping 33 world-renowned paintings from Australia to Italy to Arizona.

After 20 years, ‘I know every inch of those paintings’

First came the inspections. Before and after every leg of the journey, a team of inspectors from the Vergel Foundation and the Mexican government took note of every painting’s every flaw, filling a 27-page report of any flakes, nicks or scrapes.

But the flaws are few and minor. “They’re perfect,” said Magda Carranza de Akle, the collection’s curator. For 20 years the Kahlo paintings have been her only responsibility. She memorized the crate numbers. She knew which paintings had been slightly restored and which were entirely original. Every reported flaw, she had already seen. “I know every inch of those paintings.”

The crates had been packed and then shipped across oceans in separate wide-bodied jets. One batch made a stop in New York before connecting to Los Angeles. The other made a direct flight. In California, a climate-controlled truck picked up the paintings and made the 375-mile drive to Phoenix, tracking the temperature, humidity and air pressure along the way.

Now the collection sat in a white-walled room in the back of the Heard Museum, locked behind thick metal doors and a security guard.

‘It’s very pure’

“We are in total lockdown,” Roche said as the guard handed him a key. He pushed open one door and slipped inside, where the exhibit was still under construction. Focused employees in latex gloves measured blank patches of wall. Two men counted one-two-three and lifted a large painting, carrying it across the room. Rolling carts dotted the floor, holding blueprints of the exhibit and an assortment of drills and rulers. In the back, the Heard had set up mannequins costumed with clothes in Kahlo’s style — which reflected her indigenous heritage — and planned to hang 70 photographs of Kahlo and Rivera.

Few paintings had been hung. The rest sat on foam blocks, leaned against white walls.

“It’s very pure,” Roche said. “Very straightforward.”

And presented with exacting detail. Most art at the Heard is hung 61 inches from the floor. Roche wanted this exhibit to be hung higher, to remain visible over large masses of people. This caused great debate among the staff, but Roche won, and the paintings were raised.

They will hang at 62 inches.

‘Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’

When: Through Aug. 20.

Where: Heard Museum, 2301 N. Central Ave., Phoenix.

Admission: $7 in addition to general admission ($18, with discounts for seniors, students and children).

Details: 602-252-8848, heard.org.

MORE AZCENTRAL ON SOCIAL:Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Pinterest

Read or Share this story: http://azc.cc/2oqUND6

[ad_2]

Source link