[ad_1]

She had filled their Phoenix apartment with reminders that things could be worse, and now they were, so Katrina Taylor tried to sort through what was left. Already gone was her jewelry, the kitchen table and the motorcycle, all of it sold to make another month’s rent. Everything else went into a stack of moving boxes in the corner, waiting for Katrina to decide if they could afford to stay.

“Are we gonna move?” asked her 6-year-old grandson, Caleb.

“We’ll try to come back in the summer,” Katrina replied. “So we can get you back in school.”

“What if we don’t?”

“Well,” she said, “we’ll figure it out.”

For two years she’d somehow done that, scraping through each month on food stamps and $220 in cash assistance. Then her lease neared its final month and the landlord raised the rent by $54. Katrina, 51, knew she couldn’t afford it, but the landlord needed a month’s notice of whether she would move out or stay another year. Every other apartment she found cost even more. She couldn’t afford to stay, and couldn’t afford to move.

A flood of renters, increasing rental costs and a breakdown in government aid are contributing to difficulty finding affordable housing in Arizona and across the U.S.

Wochit

A decade after the Great Recession, Katrina had crashed into the new American housing crisis: a flood of people entering the rental market, a trend of nationwide rent prices rising faster than incomes, and a breakdown of the government program designed to bridge the gap. The federal government spends $20 billion each year on that program, distributing Section 8 vouchers that allow people to find housing and have the government pay most of the rent.

Still, the Department of Housing and Urban Development reported to Congress that 7.7 million poor American households have severe housing needs. For every 100 low-income households, there are only 39 affordable places to live.

Housing authorities across the country have filtered people into lottery systems and waiting lists to handle the demand for Section 8 vouchers, with little way to know how long the wait will be. Some Arizona families wait as long as six years. Katrina was No. 2,776 on a wait list, but the line had stalled. Every day Katrina dialed the same phone numbers and heard the same answers: She qualified for government help, but would have to wait.

MORE:HUD cuts: Goodbye affordable housing in Arizona?

Her only choice was to make it work in the meantime, scrambling to find the next step without worrying the kids. For once she felt helpless, staring across the thin line between making it in America and moving two young grandchildren to spare couches and guest rooms.

The deadline loomed. Each morning, she scrawled the date on a chalkboard propped against the wall. She had five days to decide. Four days. Three.

“Can you tell me how you feel?” Katrina asked the kids as they pulled on coats for school. They gathered around a sheet of paper on the refrigerator with six hand-drawn faces, each showing a different emotion. Kylie, her 5-year-old granddaughter, pointed at an excited-looking face, and Caleb decided he was shy. Katrina reminded herself to be home in time for her ride to a doctor’s appointment.

Soon the free neighborhood bus pulled around the corner. They climbed on for the short ride to Desert View Elementary, where the teachers seemed to care and sometimes sent Caleb home with a sack of food for the weekend. Katrina sat in the back of the bus and pulled the kids close.

She walked the kids to their classrooms and rushed back outside to catch the bus home. But the bus was late. She took out her phone to check the time, and it rang. A driver from the free service she relied on for rides to the doctor was on the other end. She was late, the driver told her, snapping over the phone. He was already waiting at her apartment.

“If you cannot stay,” she said, apologizing, “please go ahead and go.”

“I’m waiting on you,” he said again.

“I’m sorry, sir,” she said. “I can’t control this.”

For now they lived in a north Phoenix studio apartment, No. 125, down the street from a condo Katrina used to rent. She moved into the apartment two years ago, while everything was falling apart, because at $543 a month it was the cheapest she could find without making the kids change schools.

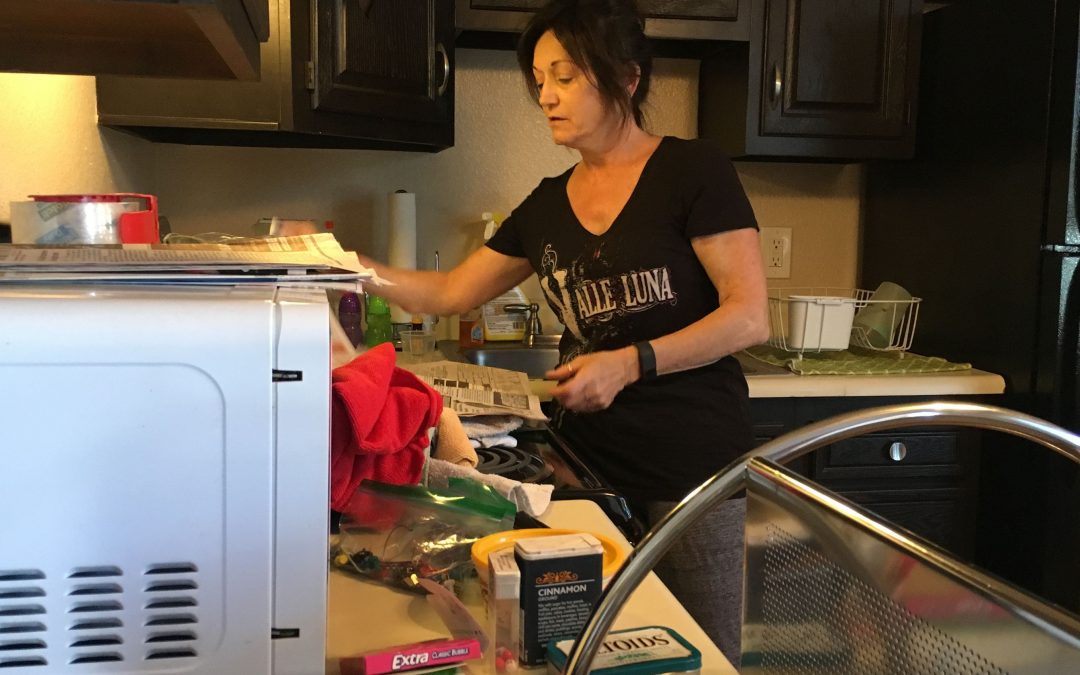

They crammed into 440 square feet, one-third the size of her old condo. Katrina hung family photos by the front door and covered the kitchen walls with cling-on platitudes. “Bless this home with love and laughter,” one read. She hid bay leaves throughout the apartment, putting them under tables and inside books, because they kept the cockroaches away.

Furniture was expensive and space was scarce, so they slept in one bed until someone at school found a trundle bed for the kids. Katrina packed while they slept. It had been months since she slept more than four hours in a night. Pressure built in the quiet, when all she could think about was the month ahead and the years that had gone by so fast.

Everything had been under control. She had done it all right: went to college, worked two jobs, raised a son. She rode motorcycles with Bret Michaels from Poison and volunteered at the homeless shelter. Life was comfortable. Secure. Then everything unraveled faster than she could adjust.

The kids’ parents had used drugs and their father, Katrina’s only son, went to prison, after he was caught stealing things from a garage to sell online. “Why don’t I handle the kids for a little bit?” Katrina offered, but now it had been two years and Katrina didn’t see herself giving them back anytime soon. Sometimes Kylie called her “Mama.” Katrina hadn’t figured out how to respond.

They were at her hospital bed a year ago, after a flurry of tiny strokes had sent her into a medical spiral. A lifetime of steroid use inflamed her intestines, but doctors couldn’t take her off them because they stifled her epilepsy. They removed her colon and made plans to remove part of her intestines every five years. She was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, Addison’s, kidney damage, diabetes. The kids wept quietly. Katrina thought she was going to die.

She left the hospital with instructions not to return to work, because the doctors worried any stress could start the spiral again. Her unemployment checks stopped coming last year. An application for disability benefits was floating somewhere in the Social Security system, as long as two years away from approval. They lived on the kids’ cash assistance checks and whatever Katrina could sell online.

Now her landlord explained that rents had to go up, that she still offered the cheapest rates in the neighborhood, that $596 a month really was reasonable, but it didn’t matter. Katrina woke up and fell asleep thinking about money and how to get a little bit of help, trying not to let the kids see her cry. She worried what damage could be done by a childhood spent without a stable home.

Already Caleb’s teachers warned Katrina that he was acting out in class, that over the past few months he hadn’t seemed like himself. Sometimes he shouted over them. Other days he just shut down.

“I want a nice, safe, clean home for them,” she said, one where the kids could have their own bedrooms and finally spend some time apart. Somewhere close to her doctors and the library. She wanted to keep the kids at Desert View.

And she could do all that, if she could hold on long enough to get a Section 8 voucher. That slip of white paper would let her rent an apartment from any landlord who would accept it, anywhere in the city. She would pay 30 percent of her income. The government would pay the rest.

But that assistance was months away, maybe a year, or two or three. Her notebook was filled with names of temporary housing that was filled to capacity. A friend offered her guest room, but then decided she didn’t want three extra people in the house and told Katrina not to come. All the low-income apartments were more than she could afford.

So they would have to move.

For a moment she thought about moving back to Utah, to the childhood home her stepfather built. But Phoenix was home now. It had been for 33 years, since she was 18 years old, drove into the city without a place to stay and slept in her car for a week.

Before she ever seriously considered going back, her nephew posted photos of the house to his Facebook page. Katrina didn’t recognize it. Everything was gone: the bright-green grass she used to play in, the trees in the front yard, the lilacs that made it feel like home.

The house was empty, left to wither and fall apart. Then it was torn down. Nobody told Katrina.

She heard the best way to get through was to keep calling, so the wait list became part of her routine: dialing and praying something had changed, always hearing nothing had. She tried again while waiting to pick up Kylie from school. No update.

She crossed off each option she had left, preparing herself to accept a little bit of help. Her youngest brother, Keith, offered a spare room in his house in San Tan Valley, an hour’s drive from her north-central Phoenix neighborhood. Katrina held to the fragile hope that she could take care of herself, but now she had just three days left.

They rode the bus back to the apartment. Katrina chose which frozen soup she would thaw for dinner, and Kylie sat with a marker and a sheet of construction paper.

“Are we going to move with Aunt Lisa and Uncle Keith?” Kylie asked, eyes locked on her drawing.

“Most likely, that’s where we’re gonna go,” Katrina said. “Are you OK with that?”

“Yeah,” Kylie said softly.

Katrina patted her on the head. “OK, we’ll start packing up your stuff,” she said. “Put it in some boxes.”

“I have junk stuff,” Kylie said. She liked her unopened Play-Doh set and the Lego collection she shared with her brother, but not much else. “It’s all broke.”

“Well, we’ll get rid of it then,” Katrina said, but still she needed more boxes for what they would keep. Her hope was fading, and moving boxes were piling up in the corner. A woman she knew at the grocery store who could get her some more, so she zipped Kylie into her coat to catch the bus again.

The 12:25 p.m. bus eased around the corner, and the door opened to reveal Kylie’s favorite driver, Dennis, in the front seat. They stepped in and Dennis pulled away. In her seat, Kylie echoed the automated messages that played before each stop. “Route 1-0-6,” she said every time.

At the store, Katrina found a man piling trays of cookies onto a table. A grocery cart of empty cardboard boxes sat beside him. “Excuse me,” Katrina asked, “do you have any boxes available?”

He pointed to the cart and said to take what she could carry. Katrina folded the boxes flat and tucked all nine under her arm, in case they had more left to pack than she thought. Some of her belongings were still listed for sale online. Some more would have to go into storage. Wherever they ended up, she thought, there wouldn’t be much room.

“You moving?” Dennis, the bus driver, said when he dropped them off, teasing Katrina as he helped her carry out the boxes.

“Yeah,” Katrina said, lowering her voice so only Dennis could hear.

“What? You can’t move!”

“Well, unless something changes,” she said, but it was getting harder to believe anything could. She had tried to live without burdening anybody, even the federal government, and found pride in taking care of herself. After the first round of seizures, she waited the doctor-ordered three months and tried to find another job. She sat in a couple of interviews, told them about her experience in administration, but no offers came.

Now she and Kylie rushed across the street and into the apartment. The bus was coming back around, and they needed to catch it to pick up Caleb from school. Katrina unlocked the door, tossed the boxes underneath a table, and headed back outside.

The bus was empty when it returned. They sat in the back and Dennis pulled away.

“Why are you moving?” he asked after a few minutes.

“Can’t afford the rent,” Katrina said, meeting his eyes in the rear-view mirror.

“I hear you,” Dennis said, because Phoenix had become one of the worst cities in the country to be poor while needing somewhere to live. The metro area offered just 21 affordable units for every 100 extremely low-income families, well below the national average, the National Low Income Housing Coalition reported. Voucher wait lists around the Valley were filled with people who didn’t know it might take years.

Katrina searched for something to say, anything to break the pressure that had been building inside of her for months. But no words came. The bus bore straight ahead, and in the back Katrina silently watched the homes go by.

By Monday, the last day, Katrina had still found nowhere to go. She opened the ragged cover of a notebook and sat at the taped-up folding table that had replaced the kitchen table she sold for some past month’s rent. In the notebook’s neat columns she had scrawled last-chance phone numbers and a list of Section 8 apartments.

Those vouchers were still years away, and somehow hope always rose again. She dialed the HUD hotline and held her breath.

An automated response clicked onto the other end. “Welcome to the wait list check system,” the voice said. Katrina tapped in her Social Security number and tried to remember her passwords as the line went dead.

“Why did you do that?” Katrina said. She dialed and again gave the robotic voice her Social Security number, then the passwords.

The voice froze. Katrina’s eyes narrowed.

“Don’t hang up,” she said, leaning forward to hover over the phone, but the system dropped the call again. She shook her head and tried to stay calm, like the doctors had ordered.

One more time she tried. The table shook on spindly legs as she knocked in her Social Security number for a third time.

“Don’t hang up,” she whispered. “Don’t hang up, don’t hang up.”

Finally the system pushed her through, and the emotionless voice read her position: No. 2,770 on the wait list. Six spots in three days.

“I went up six,” she said. “Great.”

RELATED:In one month in 2016, 27,000 applied for Phoenix rental assistance

She sank a little lower into the hard metal chair and ran a hand through her hair. Turning to a fresh page in her notebook, Katrina called up the number for UMOM, a local shelter for homeless families where she had once volunteered, before everything fell apart. Now she was on the organization’s wait list for a temporary apartment.

“What do I need to do to apply for permanent housing with you guys?” Katrina asked.

“Are you looking for shelter?” the receptionist said.

“Not really,” Katrina said. “My lease is up in March and I have really nowhere to go.”

The sound of a frantic keyboard clacked through the phone. Katrina drank chai tea from a Christmas mug and waited. When the woman came back, she sounded apologetic. There was only one program Katrina could apply for, and it required employment. But she had an idea: There was a website that aggregated affordable housing and made it searchable. Try that, the woman suggested.

Katrina pulled up the website and answered its questions. No, she clicked, she didn’t have a Section 8 voucher. No, she wasn’t a veteran. She could live with one bedroom and one bathroom. For the maximum rent she entered $250 a month, which was still more than she could afford.

We’re sorry, the website flashed. No housing was found that matched your request.

She widened the search terms, bumping the rent higher and higher, spreading further and further from the kids’ school, until she had seen them all. Low-income apartments were scattered across the city, but she couldn’t get into any of them. They were reserved for seniors, or veterans, or people with jobs. They listed expensive security deposits and application fees, or a monthly utilities bill that pushed it out of possibility. And most had their own wait lists.

On and on she searched, telling herself she could sell more jewelry and clothes to make up for it. As long as the kids were comfortable and had a place to grow up, she would make it work. “I’m not letting the kids live on the street. That’s not happening,” she said, and she filled an entire page with phone numbers of apartments she could never afford.

Before long it would be time to pick up Kylie from school and bring her home, to the small apartment where bay leaves were everywhere and moving boxes had taken up a corner. To an afternoon of homework, and another bus trip to get Caleb, then dinner and maybe a movie on the couch, because they were running out of normal days.

A deep breath, another sip of chai. She had to do it now. Sitting up straight, she held her phone with both hands and typed out the decision she didn’t want to make.

Since the rent has increased from $543.46 a month to $597.76 a month I do not believe that I will be able to afford the rent increase, so at this time I will be unable to renew my lease.

Slowly she read it over, mouthing the words to make sure the message was polite. The bus was making its way toward her apartment. She pressed send.

They were moving. It was final. Katrina put down the phone. All those years she clawed through, everything she sold online, every time they rationed food because the food stamps didn’t quite last to the end of the month, all of it gone. Their apartment, gone. Home, gone.

But she believed faith and willpower were enough. She had promised the kids they’d be back in time for school, promised herself she wouldn’t accept help for long. And there was still a page of phone numbers she hadn’t tried, so she picked the phone back up and dialed.

“I’m raising two grandchildren,” she said when someone answered, “and I’m trying to find a home.”

The month ended, and Katrina’s lease ran out.

She took the photos off the wall, emptied the refrigerator and stuffed everything she couldn’t sell into cardboard boxes. Her brother’s family parked a moving truck outside and filled it with Katrina’s bookshelves, the nightstand and the years-old television that squealed when it started up, all of it destined for a storage unit rented with her brother’s name and her last bit of hope: If she moved up the wait list quickly, she’d need her furniture.

It was only for the summer, she told herself. They would spend a few months at Keith’s house in San Tan Valley, where he had prepared two rooms: one for the kids, with two small beds and a desk for their homework, and one with a memory-foam mattress and a case of Japanese statues for Katrina.

Katrina wanted to leave her apartment nicer than when they arrived, in part because she believed in good will but mostly because the landlord still had her $99 security deposit. So she shuffled around her family and piles of her belongings, trying to erase all traces of their two years in Apartment 125.

“Am I in your way?” Keith asked.

“I just need to do this,” Katrina said, wiping a rag over a thick coating of black dust. “It’s disgusting.”

There were cabinets to empty, floors to sweep, counters to disinfect. Bay leaves were clumped in corners, by the sink, underneath the stove. She ran a broom over the walls and filled nail holes with toothpaste. The bathroom needed a sweep. She sprayed a spot that wouldn’t come off a mirror and rubbed hard with a rag. She sprayed again, rubbed again, but it wouldn’t come clean. The rag dropped to the floor. She stared at her reflection. Fifty-one-years old, and somehow everything had come to this. To three years since her last night out, to raising two grandchildren out of her little brother’s guest rooms, to sleeping four hours a night and constantly checking a wait list and waiting for help that was still years away.

“It’s strange how quickly things can change,” she whispered to herself.

A few minutes later, as she emptied the refrigerator and cleaned the drawers, a man peered through the open door. Tall and heavy, he introduced himself as Katrina’s new neighbor.

“Do you need any boxes?” he asked.

“No, I think we’re good,” Katrina said, avoiding the man’s eyes.

“I just moved in,” the man said. He pointed across the courtyard at Apartment 119, where he paid $629 a month for the same small studio Katrina could no longer afford.

“Well, welcome,” Katrina said, glancing at the now-empty apartment behind her. “And good luck.”

READ MORE:

Trump budget would cut funds used for ‘most vulnerable,’ Valley officials say

Wanted: More low-income applicants for affordable housing in Maricopa County

What is Phoenix doing to create affordable housing for artists?

[ad_2]

Source link