[ad_1]

Major League Baseball teams are bringing in plenty of money, according to Forbes’ newest value list.

USA TODAY Sports

CHICAGO — They gathered in two dugouts in Chicago this week, representing not only every component of the game but also perhaps the hope and future to help heal Major League Baseball’s ongoing shortcoming: the scarcity of African Americans playing baseball.

While baseball celebrates the 70th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier Saturday with glorious ceremonies and a statue unveiling at Dodger Stadium, it will only camouflage the harsh reality that there are fewer African Americans in baseball than at any other time in the last 60 years.

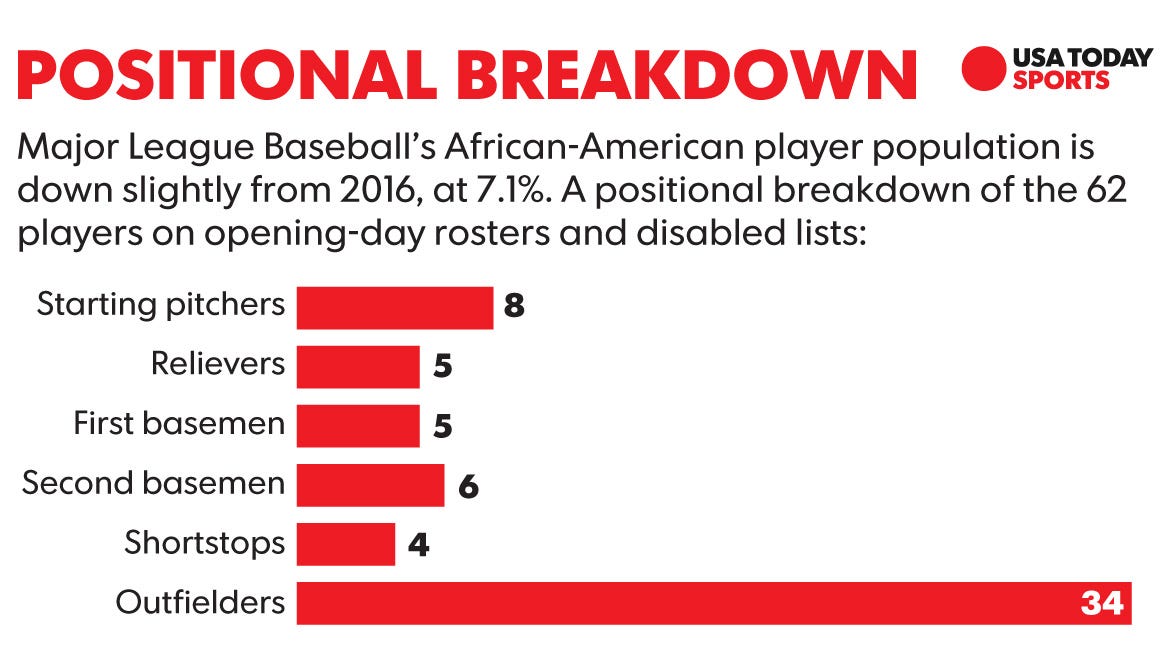

African Americans comprise just 7.1% of players on this year’s opening-day rosters, the lowest percentage since 1958, according to a study by USA TODAY Sports.

MORE MLB:

There are 62 African-American players among the 868 on active rosters and disabled lists. Eleven teams have no more than one African American on their roster, and the San Diego Padres and Colorado Rockies have none.

“That’s unbelievable,” says the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Dave Roberts, who with the Washington Nationals’ Dusty Baker are baseball’s only African-American managers. “You ask yourself, ‘Why is this happening?’”

There are a litany of reasons why the African-American population in MLB has dwindled from 17.2% in 1994, according to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), but there are signs of optimism. Six of the top 30 prospects in this year’s draft, according to ESPN and MLB

.com, are African American — including perhaps the top three picks. Five of the top 12 high school prospects, Baseball America reports, are African American.

Baseball also is starting to see results from the millions of dollars it has poured into youth programs, urban initiatives and showcases. This will be the third consecutive year that an alumnus from the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities program and Breakthrough Series will be selected among the top five picks, with Los Angeles high school pitcher Hunter Greene likely one of the the first two players chosen.

Yet if baseball really wants to make inroads, there’s no reason to look any further than five men in uniform this week during the Dodgers-Chicago Cubs series.

You had an African-American manager in Roberts, who could not even get an interview from his own team in San Diego but became the National League manager of the year in 2016.

You had Cubs outfielder Jason Heyward, a childhood prodigy out of Atlanta who is the highest-paid position player among African-American players.

You had Cubs reliever Carl Edwards Jr., one of only 13 African-American pitchers in all of baseball and one of five relievers.

You had Dodgers first-base coach George Lombard, the grandson of the former dean of Harvard, whose mother marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in the Civil Rights movement.

And you had Andrew Toles, who two years ago was making $7.50 an hour working in the frozen foods section of a grocery store in Peachtree City, Ga., and is now the Dodgers’ starting left fielder.

These five might be young, but they will embrace the challenge of ushering in a new generation of African-American players and managers.

“I’d love to make a difference,” says Edwards, 25. “I actually love being a minority in this game as one of the few black pitchers. I know everybody wants to hit homers and be on the field making great plays, but I love pitching. You’re the center of attention.

“In my hometown (Prosperity, S.C), I see all of these kids wearing No.6 on social media like me. Hopefully, by them watching more, more minority kids will want to become pitchers, too.”

Gallery: Scenes from Jackie Robinson biopic ’42’

Just 1.5% of all players in the game today are African-American pitchers, and, according to Mark Armour’s research with SABR, there are 10 times as many Latino pitchers as African Americans.

Toles, the son of former NFL linebacker Alvin Toles, was released by the Tampa Bay Rays in 2014, but after being out of the game for a year he made the meteoric rise from Class A to the Dodgers.

“It’s tough to get where I’m at obviously, and when you’re an African American, depending on your upbringing,” Toles says. “But the way I was raised, I’m not a quitter. Once I start something, I finish it. I definitely consider myself a role model now.”

Says Roberts: “I think a lot of young African Americans can relate to him. Hopefully he can inspire others with his story.”

Roberts, who had the most famous stolen base in Boston Red Sox history in the 2004 playoffs, spent 10 years as a player and five in front offices and coaching staffs. He wasn’t even considered for the managerial opening of his own San Diego Padres and was considered a long shot when interviewed by the Dodgers. Yet he dazzled the Dodgers ownership and front office with his intelligence and charisma in the interview process and was hired as the club’s first minority manager.

Now, he wants to help those behind him and see a greater representation of African-American managers, and minority managers, in the game. Of the 30 major league managers, 27 are white.

“I’ve tried to motivate and inspire these coaches who potentially have the ability to manage and hopefully get that opportunity like I did,” Roberts says. “Having more African-American leaders would be a good thing in this game.

“It’s like when I came up, there were so many guys you looked up to. You need veterans who have that presence and leadership that can impact a clubhouse.”

The most impactful African-American leaders among position players these days are Adam Jones of the Baltimore Orioles, Curtis Granderson of the New York Mets, Andrew McCutchen of the Pittsburgh Pirates and Dexter Fowler of the St. Louis Cardinals.

Heyward, who signed an eight-year, $184 million contract with the Cubs before the 2016 season, certainly could join that group. He is just 27 but showed leadership skills by calling a team meeting during the infamous rain delay in Game 7 of the World Series, helping the Cubs to the championship.

“I know the game is trying to get younger, and you’re already seeing a trend,” Heyward says, “so I think that will help with so many young, athletic guys. I’d love to make a difference, too.

“The big thing to me is we could get colleges to give more baseball scholarships. If you want to go to school and get your education, baseball is not going to pay for it. They don’t have enough scholarships (111/2). So you have to play football and basketball to get a chance for a college education if you don’t have the money for school.

“If we could ever change that, that would really help.”

And, of course, it would be huge simply to educate kids on the benefit of playing baseball compared to football. Sure, the bus rides are long in the minors, and it might take years to reach the big leagues, if at all. But once you arrive, the average salary is about $3.5million. And, unlike football, the contracts are guaranteed.

Every single penny.

“That’s the biggest thing is just educating and teaching the kids at a young age,” says Lombard, who was a USA TODAY All-America high school running back in Georgia. “I think the Urban Youth Academies are outstanding, bringing the sport to some of these inner cities. There are so many great athletes that come out of Miami, where I live, but they don’t grow up playing baseball because they don’t think it’s a cool thing to do.

“We’ve got to change that and tell them the benefits of playing the sport. I had seven or eight surgeries in my career, and I played 16 years. If you had one of those injuries in football, they just move on to the next guy.

“I know I want to help. I think all of us do. And I really believe we can help make a difference.”

In the name of Jackie Robinson, baseball can only hope.

[ad_2]

Source link